What is: a near miss?

First published in Health and Safety at Work Magazine, October 2012, with heavy editing in 2022. If you want a quicker read, you can leave out the parts in the grey boxes.

Bridget Leathley looks at when the trivial becomes a near miss and when a near miss becomes an accident.

Why do near misses matter?

In the now somewhat dated publication from the HSE (2004), HSG 245, Investigating accidents and incidents, explains the importance of investigating near misses:

Learning lessons from near misses can prevent costly accidents.

The Clapham Junction rail crash and the Herald of Free Enterprise ferry capsize are both cited as examples of where ‘management had failed to recognise, and act on, previous failings in the system.’ With the evidence we have in 2022, we could add to that Grenfell Tower, where the UK government consistently failed to act on multiple failings in the system of building regulation.

HSG 245 goes on to list legal reasons and operational benefits of investigating, although their list mixes up investigation of accidents with near misses. Benefits that relate to near misses include:

- An understanding of the ways people can be exposed to substances or conditions that may affect their health.

- A true snapshot of what really happens and how work is really done.

- Identifying deficiencies in your risk control management, which will enable you to improve your management of risk in the future and to learn lessons which will be applicable to other parts of your organisation.

The classic accident triangle (Figure 1) provides a useful reminder of why it is important to report and investigate near misses. You have probably see the triangle with different numbers of layers, and with different numbers in each layer, depending on the data used, but a simple version illustrates the key principle. (See my article on Heinrich’s accident triangle for a reflection on modern criticism of the triangle.)

The chance to learn from the investigation of a death is an opportunity no health and safety professional would seek, and that most of us will never have. Nationally, and within particular industries, numbers of deaths may be a (lagging) indicator, but a single large accident, or changes in the economy leading to a reduction in the workforce can cause figures to vary enormously.

Though recording and investigating injuries presents a more detailed picture, this is still a lagging indicator — measuring after the event. And in small organisations, recorded injuries may only be in single figures, making small, chance variations appear significant and providing few learning opportunities.

Recording and investigating near misses, on the other hand, not only helps you to assess the strength of your safety management system but also provides an opportunity to fix problems before injuries occur. At its most simple, reporting the frayed carpet that nearly tripped someone can trigger a repair to prevent the accident in which someone actually trips. Likewise, if someone noticed that many train drivers missed the same red signal at the same place on the many occasions where the train went on to arrive safely, something might have been changed before a driver missed the signal with fatal results.

There is little disagreement among safety professionals on the need to report, record and assess near misses to improve safety. But there is confusion on the detail: what is a near miss? Understanding what falls into the category of things worth reporting is essential if your near miss reporting system is not to be either overwhelmed with trivia, or ignored as an administrative overhead.

What is a near miss?

A near miss is most often defined in contrast to other terms. The key definition of a near miss is provided in HSG 245, in contrast to an accident and an undesired circumstance:

Accident: an event that results in injury or ill health

Near miss: an event that, while not causing harm, has the potential to cause injury or ill health.

Undesired circumstance: a set of conditions or circumstances that have the potential to cause injury or ill health, eg untrained nurses handling heavy patients.

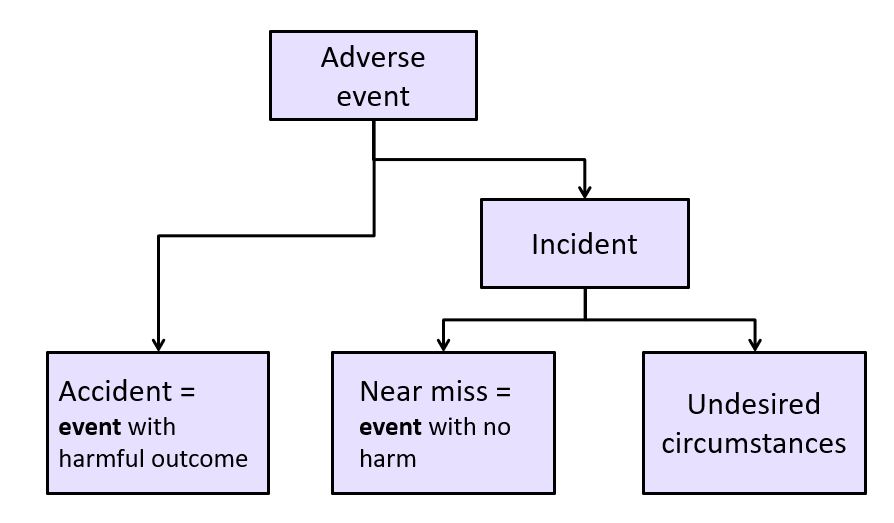

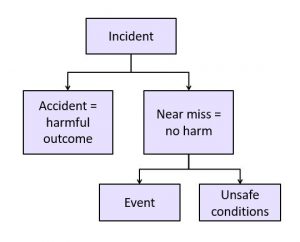

In HSG 245 near misses and undesired circumstances are collectively referred to as Incidents, and near misses include specific, reportable adverse events, as defined in the Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations. I’ve represented the relationships between these terms in Figure 2.

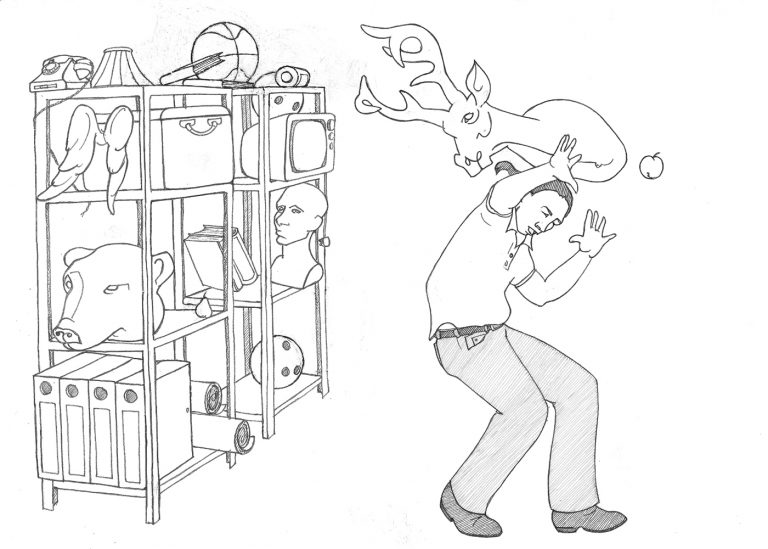

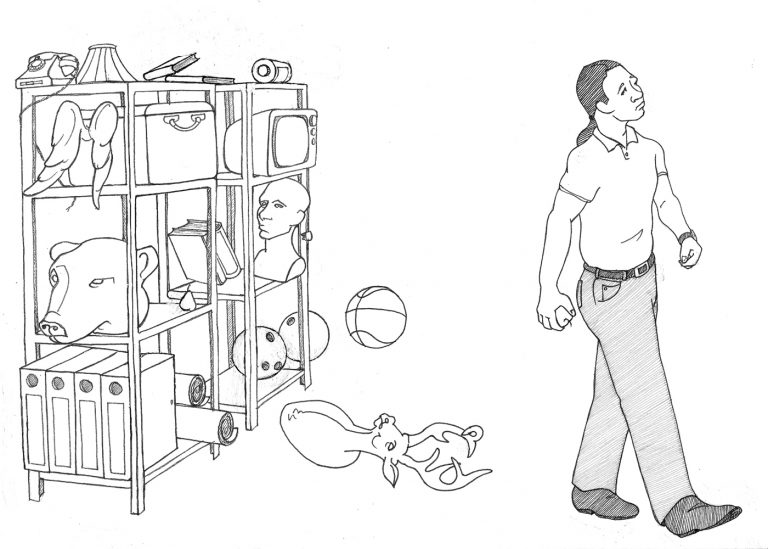

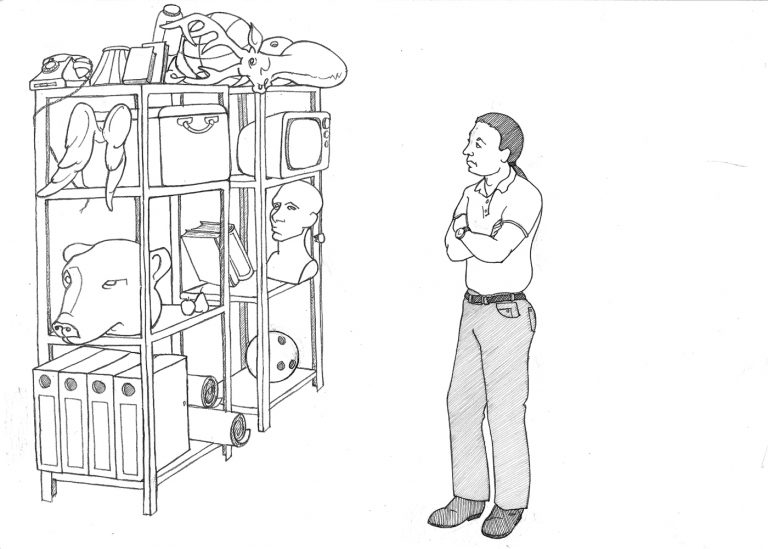

The illustrations in HSG 245 relate to construction, showing bricks falling off scaffolding onto a worker below (indicating an accident), bricks falling near a worker, indicating a near miss, and bricks badly stacked on scaffolding, indicating the undesired circumstance. A talented friend of mine produced a parallel set of illustrations, as shown.

An accident, a near miss and an undesired circumstance

Figure 3: Illustrations of accident, a near miss and an undesired circumstance. Thanks to Jeannie Banham for the drawings.

While the construction illustrations in HSG 245 and the scenarios shown here make a clear distinction between the near miss and the undesired circumstance, the example given by the HSE is less clear. Is an untrained nurse handing a heavy patient really only the “undesired circumstance”? I would argue it is the near miss – the undesired circumstance is having staff who are not trained to do tasks they might need to do, or a workplace that relies on manual handling for a task that requires equipment.

In practice, few organisations I have worked with use the HSE taxonomy. Making a distinction between an “event” that could have caused harm, and an “undesired circumstance” that could cause harm is an unnecessary complication. Look at the illustrations in Figure 3 – in the last image, the deer head didn’t appear there overnight. There must have been an “event” of someone placing the deer head on the edge of the shelf, or adding something to the shelf that pushed the head towards the edge.

There is a further contradiction in that, having said in the definition that only the accident and the near miss are related to events, the HSE define all three as “adverse events”. While some confusion has been ironed out (see Poor historical definitions) a more common taxonomy is represented in Figure 4. In this, organisations have ‘incident reporting systems’ which request people to report both accidents (where harm occurs) and near misses (where no harm has occurred, but could). The definition of the term “undesired circumstance” might still be useful, but as a type of near miss.

Poor historical definitions and complex academic ones

When I wrote the first version of this article in 2012, the HSE had a contradictory definition (in a document referred to as IGN 1.08) of a near miss as:

Any incident, accident or emergency which did not result in an injury but had the potential to cause harm.

Compare this to the definitions in HSG 245 (which had been published in 2004) and you can see the confusion: in HSG 245 an accident necessarily resulted in injury or ill health; in IGN 1.08 an accident might not result in an injury. I like to think that someone from the HSE read my article, appreciated the contradiction, and removed it. You can no longer find IGN 1.08 or the contradictory definition on the HSE website. However, you will still find it in the safety documentation of many organisations (and on websites that plagiarised my original article without making their own checks).

You can see where this idea comes from. When my son was younger, he broke a precious ornament. He defended the careless act as “an accident.” He was not considering the extent of injury to a person; he was explaining that the event was unintended. Whether or not someone was hurt by the shards of pottery did not alter the accidental nature of the event. This presents a completely different definition of an accident — that which is accidental. In the original article I illustrated this definition with a diagram, but as it is no longer in use by the HSE, I feel it is no longer relevant.

Another definition referred to in the original article was from INDG 453, Reporting accidents and incidents at work. The 2012 edition provided this illuminating text:

An accident is a separate event to a death or injury, and is simply more than an event, it is something harmful that happens unexpectedly.

As I commented at the time, never has the word “simply” been so out of place. And whether the event was an accident waiting to happen, or unexpected, is also not relevant to any meaningful definition. This confusing definition was removed a year later in the 2013 edition of INDG 453.

Academics have an even more complicated view of near misses. In The Human Contribution James Reason outlines four types of “error outcomes”. The first two types refer to outcomes where the results could have been harmful, but in the event there was no harm. He calls these “exceedances” where the error was at the edge of a known range of equipment or human behaviour (doing something too fast, too high, too much) or “free lessons” for less well defined “inconsequential unsafe acts”.

The third category Reason calls “incidents”, which he describes as “events of sufficient severity to be reported”, admitting there is no general agreement on what counts as “sufficient”. He goes on to suggest that incidents tend to involve some financial loss or damage to equipment or production, and may even cause “minor harm” to people, but nothing too serious.

The fourth category is “accidents”, which are events with significant adverse consequences, including injury and death.

A clearer definition of near misses

The other important part of the HSE definition to note is the reference to the Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (RIDDOR). Schedule 2 of RIDDOR provides a detailed description of what type of occurrences are considered dangerous enough to report, including some failures of lifting equipment, pressure systems and scaffolding, as well as some incidents involving explosives, biological agents and breathing apparatus.

Reporting only these “dangerous” near misses, however, is not sufficient in a proactive system of safety management. To be useful, the definition of “near miss” must be broader than the dangerous occurrences in RIDDOR.

When I wrote the first version of this article in 2012, amongst the less useful advice on the HSE website, there was a more satisfactory definition of a near miss from PABIAC (the Paper and Board Industry Advisory Committee). PABIAC wisely left out any reference to whether or not an event could have been expected (unlike the old INDG 453 version) and instead focuses on what stopped the miss from being an accident:

An unplanned event or situation that could have resulted in injury, illness, damage or loss but did not do so due to chance, corrective action or timely intervention.

Although on checking in 2022, I can’t see this definition anywhere on the HSE website, it has found its way into the policies and procedures of multiple organisations. In the USA there is a similar feel to the definition given by Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA):

.. incidents .. in which a worker might have been hurt if the circumstances had been slightly different.

OSHA use the term “close call” as well as “near miss” for such incidents. The essential part of the PABIAC and OSHA definitions that is missing in HSG 245 is the likelihood that the incident could have been worse. While this is (like most risk assessments) subjective, it is a useful rule of thumb to prevent a reporting system from being overwhelmed with trivia. For example, if I bump into a table, and nearly bruise my thigh, it is hard to think of a situation that would have been any worse than this. If the top stair on a busy staircase is damaged or slippery, such that I have to catch myself to prevent a fall, it is easy to see how the injury could be a lot worse.

Understanding 'harm' so that you can understand near misses

If the distinction between a near miss and an accident is whether harm is suffered, there needs to be a clear agreement on what is meant by harm. If we take the definition to mean only harm to health and safety, then the Buncefield explosion in 2005, estimated to cause over £1 billion of damage, was a near miss.

When a fire destroys an entire factory, but everyone escapes promptly with not so much as a bruised knee or case of smoke inhalation, this is a near miss for those concerned only with the safety and health of people. For others, any fire or explosion, any damage to equipment, property or environment and any interruption to business, services or production are accidents. Some organisations consider an even wider range of outcomes, such as reputational damage or the potential for legal action. The definition used by European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) is clearer that harm goes beyond health and safety issues, by including damage explicitly:

an unplanned event which did not result in injury, illness, or damage – but had the potential to do so.

For each category of harm — injury, illness and damage — a near miss reporting scheme must include clear guidelines on how much harm is insignificant. Is a paper cut or a bumped knee a near miss if no work time is lost? For psychosocial hazards, this decision can be very subjective. One shop worker may wish to report a verbally aggressive customer whose behaviour left them shaken and fearful, while another worker may laugh off the same incident. Is a shattered coffee mug sufficient damage to be an accident, or does the damage have to pass a financial threshold, or have safety implications?

Some schemes are very specific in defining what people must report as near misses. Those working at height, for example, may have a specific requirement to report any dropped object, however small, from whatever height. Other schemes are much more general, perhaps having “incident books” used to collect information as varied as what time someone arrived on shift and what messages have been passed on, to records of equipment alarms and first aid incidents.

The more you specify, the more you may limit what people report, but no limits may result in an avalanche of reports that are difficult to manage. So decide carefully what you are prepared to act on. Make sure your rules are consistent. In one organisation where I was asked to teach members about reporting requirements I found that the rules led to an interesting paradox:

- One document stated that “all near misses should be reported”

- Another document stated that “minor injuries do not need to be reported”

So if the deer head in my illustrations dropped on my shoulder and caused a minor accident, it wouldn’t need reporting, but if it missed, it would. The organisation did change both these statements, with the emphasis on sharing near misses from which lessons could be learned.

Table 1 illustrates one way you could explain to people in a particular workplace the scope of what you want reported as a near miss.

| Type of near miss | Example |

|---|---|

| Hazardous event occurs, but harm is avoided by chance | The pallet on the shelf has been badly stacked, and when you try to get the forks underneath, the load falls on the floor next to your forklift |

| Hazardous event is avoided, but the hazard remains | You notice that the pallet has been badly stacked, so you get inventory from another location |

| Hazardous event is avoided and the hazard is removed | You notice that the pallet has been badly stacked, so you arrange for someone to use an access tower to remove items individually |

| Hazardous event is avoided only by timely intervention | Someone is about to load the shelf with a badly stacked pallet, and you stop them before they do so |

A near miss by any other name

A further debate is over whether “near miss” is the correct term. Synonyms to look out for include: near hit, near loss, undesired circumstance, close shave, close call, narrow escape and potential (error, event or accident). Looking at the issue the other way around, some organisations refer to the reporting of near miss events or circumstances as good catches or safety observations. These terms change the emphasis from “spotting things that have gone wrong” to “spotting opportunities for improvement.”

Industry-specific examples of near misses have their own names — SPADS (signals passed at danger) and CIRAS (Confidential Incident Reporting and Analysis System) on the railways or AirProx for the airline industry.

Near misses can feed optimism

While the purpose of reporting and investigating near misses is to identify weaknesses in our health and safety management systems, near misses can feed an optimism bias.

Near misses can make us think we are already resilient. In the first two decades of the twentieth century Europe watched the rest of the world coping with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), swine flu, Ebola and avian flu. That these illnesses didn’t impact most Europeans perhaps led to a false sense of optimism – that we didn’t need to plan for such events. We were somehow different. COVID-19 showed us otherwise. When Hurricane Ivan turned aside from New Orleans in 2004, the authorities appeared to dial down their preparation for a hurricane, rather than plan to deal with the impact of Hurricane Katrina a year later. That climate change is already having an impact in parts of the world, but we are largely unaffected leads us to avoid making any major changes. At the level of occupational health and safety, that staff work around slippery floors, uneven steps, unguarded machinery or standing on furniture to reach a height makes us think that it must be ok. How many times are we told as safety professionals “we’ve not had an accident so far”?

While it’s good to have a generally positive outlook on life, when reviewing near misses, some pessimism can be useful. Start my asking “what is the worst thing that could have happened?” The sense of realism comes by the follow-up questions – for the worst outcome, what else what need to have failed, and what controls would prevent further failure?

Improving near miss reporting

By this point you should have decided what to call a “near miss”, how to define the term, and what types of near miss you want reported. How do you get people to start reporting?

Traditional near miss reporting systems are paper-based. Forms are completed, left in in-trays, and the near misses are investigated with a “last in – first out” approach. Setting targets for the number of reports that need to be made is counter productive – such reports tend to absorb investigator time, while being of little value in improving safety and health in the workplace.

Many organisations have moved over to computer-based reporting systems. While some require users to log in to a desktop PC to log an incident, the best systems allow anonymous reporting without a login, for example on kiosk systems on a factory floor. Others do require the details of the reporter, but capture these and other information automatically, where a user is already logged into a system. Using technology can go a long way to improving near miss reporting, but as with any technology solution needs to be introduced through consultation. The EAST framework provides some clues as to how to improve near miss reporting, as shown in Table 2.

| Easy | Not everyone works at a desk – you are most likely to have the near miss or spot the unsafe conditions when you are away from your desk. By the time you get back to your desk, dozens of emails need to be read and dealt with. Is reporting the oil leak on the warehouse floor your top priority? Systems which make it easy to report on a mobile phone make it more likely that near misses will be reported. Pull-down lists tailored to the workplace make it easier to add key information - and make the reporting process leaner by pre-defining categories. |

| Attractive | No one likes hassle. Incident report forms that ask for your name, the date, the location and even your date of birth, role, department and contact details make the whole idea of reporting less attractive. A form which already knows the name of the reporter (and any other personal information), the date and the likely location will reduce the effort needed to report. |

| Sociable | Setting targets for individuals to report near misses tends to result in poor quality information. Set team targets around quality rather than quantity. Give teams time to discuss improvements and to propose solutions. Give all employees feedback about positive steps taken because of near miss reporting. A reluctant reporter might change their mind when they see that a team has been given improved equipment or processes as a result of reporting. |

| Timely | The quicker you can get the report, the more accurate the information is likely to be – and the more likely you can prevent an accident. Mobile reporting allows people to make reports immediately (although check how the system copes when there is no wifi or mobile signal). Timely feedback will encourage more people reporting. Let people know about improvements made because of their reporting – or where you can’t do anything, explain why. Identify some quick wins to show people their reports made a difference. |

Further reading

If you found this useful, take a look at other articles in my What is? series:

- What is a hazard?

- What is foreseeability?

- What is a control?

- What is reasonably practicable?

- What is significant?

- What is suitable and sufficient?

- What is competence?

- What is Heinrich’s accident triangle?

You might also like the the Lexicon series in IOSH Magazine useful, starting with A is for ALARP and relevant to this topic, N is for Near miss.