Learning & forgetting: the problem of skill decay

First published in Health and Safety at Work Magazine, September 2017. Illustrations updated 2021

Not all acquired knowledge sticks around: anyone fancy a GCSE maths resit? But when the skills are safety critical, managers need to understand the concept of skill decay and how to tackle it, says Bridget Leathley.

The problem of skill decay

Dr Kenneth Lawani and Professor Billy Hare from Glasgow Caledonian University raised the problem of skill decay, citing it as a possible factor in the deaths of two technicians who fell from height while working on wind turbines. The problem is not limited to high hazard industries: there have recently been two recent fatalities involving mobile elevated work platforms (MEWPs), where an initial crush was compounded by colleagues’ inability to use the emergency lowering controls.

The research project by Hare and his colleague Kenneth Lawani from Glasgow Caledonian University (GCU) on the wind turbine sector has shown that skills can decay relatively quickly. Current guidance, from trade associations RenewableUK and the Global Wind Organisation (GWO), requires operators to have work at height and rescue training every 24 months. But the research project found that, with no refresher training in between formal training, even a month after training, average proficiency was around 74%, and at three months down to 68%. At the point just before the two year refresher training would be due, skill competence could be as low as 35%, a gap that could well make the difference between a successful rescue and a fatality.

But what about industry guidance?

In various specialist fields, industry bodies develop specific guidance. For instance, the Offshore Petroleum Industry Training Organisation (OPITO) publishes guidance for the training of offshore installation managers or OIMs, who are ultimately responsible for protecting people and the environment on an installation. It stipulates refresher training every two years for emergency response team leaders and team members, a four year interval for the Basic Offshore Safety Induction and Emergency Training, and no expiry date for the OIM Controlling Emergencies certificate, other than a requirement to participate in at least one emergency exercise every three years.

But when Maureen Jennings, an experienced engineer in the offshore oil and gas industry, conducted postgraduate research at the University of Aberdeen, she was forced to question the received wisdom on refresher training, finding no validated evidence for the different intervals. And the courses themselves might not match the workers’ circumstances. In reviewing the 2006 explosion on the Rough 47/3-B gas storage installation operated by Centrica Storage in the North Sea, Jennings found that while the lifeboat coxswain had recently received refresher training, the course did not include the specific steps needed to launch the lifeboat on the Rough installation. He had been trained on lifeboats with an electric start mechanism – the hydraulic mechanism on the Rough installation needed an extra step to open a valve first.

Skills have a half life

As a health and safety manager, how do you decide how often to retrain staff? Can you rely on the expiry date on the training certificate, or the advice of an industry-led sector body, or should you be doing more? What does research tell us about skills acquisition and skills decay? And does new technology offer solutions that can predict the need for training, and deliver it in a fresh way?

The relevant guidance is non-prescriptive: since health and safety legislation is largely risk based, it is not surprising that regulations and guidance are not more specific. The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (MHSW) require employers to ensure that employees are provided with “adequate health and safety training” when they join an organisation, and later when exposed to any new or increased risks.

Alongside the requirement to provide the training during working hours, the Management Regulations require that it be “repeated periodically where appropriate”, leaving the interval to the employer’s discretion.

In many areas, there are no prescribed or even recommended intervals for refresher training. The Work at Height Regulations, for example, specify only that people receive “adequate training” in rescue processes, leaving the definition of “adequate” to individual health and safety teams. In some specific areas, however, the regulations do offer more advice. For example, L143 Managing and working with asbestos says that those working with asbestos should have refresher training at least once a year. However, for those needing only asbestos awareness training, there is no such requirement, but “some form of refresher awareness should be given, as necessary.”

INDG 462 Lift-truck training mentions but does not spell out “reasonable intervals” for training lift-truck operators, saying that “even those who are trained and experienced, need to be routinely monitored and, where necessary, retested or refresher trained to make sure they continue to operate lift-trucks safely”.

How much is enough?

For first aid, the most general emergency skill, certificates are valid for three years. However, the HSE recognises this might be too long and “strongly recommends” that first-aiders undertake at least a half day of refresher training every year to “maintain their basic skills”.

Clearly, there is a distinction between skills that are reinforced by daily practice and usage – for instance, the daily use of a lift-truck reinforces initial training – and the skills needed in other specialisms, which might only be used when an emergency arises. For instance, lifeboat coxswains, wind turbine operators and OIMs would never need their emergency rescue skills unless there was an emergency, so simulations are needed to practise those skills.

For any health and safety manager trying to determine the “appropriate” intervals for safety critical tasks, we need to understand more about how we learn – and how we forget.

Rollercoaster curves

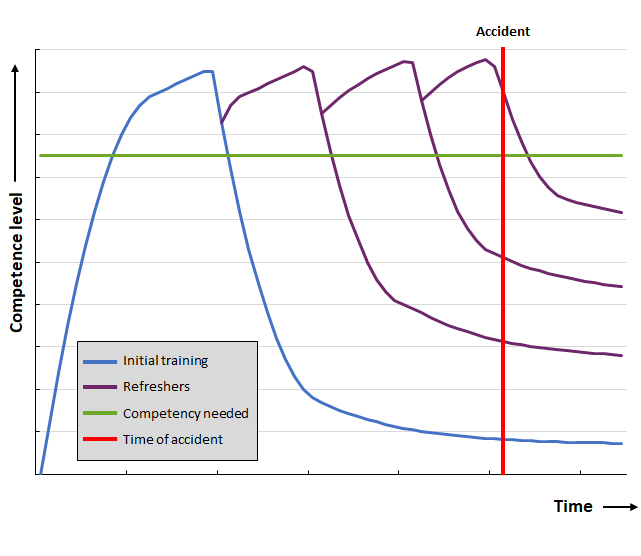

The graph above portrays the “learning and forgetting curve”, a hypothesis based on experiments by German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus. As it suggests, when learning a new skill, there is typically an initial steep curve for skills acquisition, indicating that we become more knowledgeable or proficient. Over time, this slope becomes less steep – it is more difficult to take new information in, and we reach our maximum proficiency for that learning period.

The forgetting curve unfortunately follows a similar pattern: our proficiency drops quickly immediately after a learning period, and then levels off, dropping more slowly as time goes on. As the red line indicates, the longer the time interval between practice and performance, the greater will be the skill decay.

Revision and refresher training is therefore an attempt to stem the downward trend of forgetting. The graph shows how successive revision sessions can re-enforce the initial learning, with the result that each time we peak a bit higher, and the forgetting curve bottoms out in a position that suggests we are more proficient.

In their research looking at wind turbine technicians, Hare and Lawani measured knowledge retention, as well as skill retention. Perhaps surprisingly, they found that the forgetting curve was less steep for knowledge than for skills. In other words, after three months trainees scored better on knowledge tests than on skill tests.

To explain this, we need to look at the types of skill. Once you have learnt to ride a bike, you never forget because this is a “continuous motor skill”, which involves the repetition of a movement pattern. However, making use of a rescue harness or launching a lifeboat is known as a “procedural task skill”, involving a series of discrete responses. While continuous motor skills decay slowly, procedural skills decay much more rapidly unless they are practised frequently.

Maeve O’Loughlin, senior lecturer in environment, safety and health at Middlesex University, believes these distinctions between types of skill and knowledge are important. “Complex procedural skills need to be measured against a competency model, and refreshed accordingly. For knowledge and rules, annual refresher training is not only unnecessary, but counter productive, as workers disengage, seeing it only as the organisation’s attempt to protect itself legally.”

So, how do you maximise the learning and minimise the forgetting? In an ideal world, having determined the proficiency required for an emergency skill, training would be repeated as often as is necessary to maintain the skill above the minimum acceptable standard (the red line on the graph).

However, as the Hare and Lawani studies indicate, this might require training exercises every month. Fred Sherratt, senior lecturer in construction management at Anglian Ruskin University, suggests a pragmatic reason why companies don’t do this: “Any rescue or emergency kit is invalidated by one use and so companies don’t like to get it out of the bag as they then have to get a new one.”

Where workers need to be reminded of rules and facts, tool box talks, e-learning and other nudges might be appropriate, spaced out in short bursts throughout the year, rather than a generic annual refresher. But for procedural skills, nothing beats practice. Some emergency skills are also dangerous to practice, exposing people to falls from height, smoke inhalation or manual handling injuries.

Skill decay is a fact of life, but an awareness of the concept and its effect is essential to health and safety managers. And while there may be guidance out there, it might not necessarily be aligned with an organisation’s needs, or its culture. An approach that recognises diversity, of both needs and training media, might be the best way to combat skills decay. We’ve compiled five ideas that safety managers can apply to mix up their training offer.

Mixing it up

1. Overlearning

“Overlearning” involves practising a skill beyond mastery to the point where it becomes automatic. To do this with a procedural task skill, with complex steps and few environmental cues, takes a lot longer than learning a continuous motor skill. The additional hours of sustained practice to perfect performance must be balanced against the added benefits. Look at that learning curve again – once it starts to plateau, a lot more effort is required to gain a little more mastery, and this can be demotivating for trainees, as well as expensive for employers. Lawani points to other research that suggests that performance can be improved and maintained by giving trainees better feedback about their performance errors.

2. Varying the frequency of refresher training

If it is not practical to provide refresher training to everyone every month, employers might choose to focus extra training where it is most needed. Options include:

Role-based: For example, fire wardens might be given more frequent evacuation practice than general staff.

Proficiency (or error based): For routine tasks, such as driving, observations of competence can be a trigger for more training. For emergency training, knowledge-based tests could be given to determine who needs additional skills training, but the links between knowledge and skill would need to be verified.

Task-based: Concentrate on the emergency tasks most prone to skill decay, and the elements of the task that are most critical.

- Experience-based: Those attending refresher training for the second or subsequent time have a less steep forgetting curve than those training for the first time. Lawani and Hare’s research showed a steeper drop for those training for the first time, compared to those who had trained before. Refresher periods could start short, and extend over time – for example, three-months for someone new to the industry, up to three years for someone in the industry for 20 years.

3. Job based cues

The ergonomic approach is to make the task less difficult to learn, and to provide environmental cues as to what to do. For example, some height rescue kits are sold with the promise that they require less skill to use. When comparing the cost of rescue equipment, the cost of maintaining competence must also be considered – the more expensive equipment might reduce your training budget in the long term.

Although it would be unwise to rely on people reading instructions in an emergency, some cues can be provided to remind people of the emergency actions required. We are familiar with the idea than an emergency stop button should be red and yellow, and other conventions such as working from left to right can be useful (although cultural differences must be considered).

4. Use of models

Resuscitation dummies and training defibrillator units for practising cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) are common, but will only be relevant in a minority of training scenarios: dummies and practice harnesses have not made their way into most work at height training.

Emergency scenarios can be rehearsed via table-top exercises, perhaps with drawings or models to aid visualisation. Some trainers even make use of toys. Stephen Jenkins, at health and safety consultancy RHSS and a former commanding officer of the Cherbourg Naval Fire Brigade, says that he used a child’s fire engine to consider how aerial and turntable ladders could be positioned in different emergency situations.

Jenkins explains: “The real appliances aren’t always available for training purposes, so the toys allowed ‘hands on’ training while still being in a classroom.”

Warren Fothergill, a compliance and training manager at ACS&T Logistics, also saw a benefit in using toy cranes to teach plant operatives about the centre of gravity when training in Oman, where English wasn’t the first language. “It visibly demonstrated what failures occur and the impact of mast heights and boom length on risk.”

An advantage of using small scale models rather than the real equipment is that students can test the effect of making the wrong decisions, which would be too dangerous to try with the real thing.

5. New technology

While it is not practical for most organisations to run full-scale emergency simulations on a regular basis, and models or toys don’t always have the right physics for a realistic simulation, emerging digital technologies offer further possibilities. Airline pilots have made use of simulators to practice their full range of skills for a hundred years, and simulators are also used for process control (see HSE, RR086, Competence assessment for the hazardous industries).

Video and model-based simulations are now being used to allow surgeons to practice medical procedures, while 360o rooms, 3-D glasses, and augmented and virtual reality are all becoming more affordable options. In the construction, infrastructure and utilities sectors, early adopters are already trialling the technology, such as contractor Skanska’s experiments with the Hololens headset.

E-learning courses have become a familiar way of refreshing knowledge, and mobile apps now make such learning available in regular, bite size doses. In a Korean study published in Resuscitation (Ahn et al, 2011) students were trained in CPR and defibrillator (AED) use. At retest three months later, those who had watched video clip reminders on their phone performed better, and expressed more confidence than the control group.

At Glasgow Caledonian University, Hare says that he is keen to develop virtual reality simulations to provide lower cost ways to practise rescues from height. As this technology becomes cheaper, this could become a practical solution for safety managers in many sectors.