What is: competence?

First published in Health and Safety at Work Magazine, May 2012

Bridget Leathley continues our series on the base concepts of UK safety regulation, looking at what makes a person fit for a task.

Not knowing what constitutes competence can be costly in financial and human terms. In January 2013, Prior Scientific Instruments and its health and safety consultant, Keith Whiting, together paid more than £14,000 in fines and costs for failing to protect the company’s employees. Whiting was not competent to provide appropriate advice on hazardous substances, and the employer had not taken reasonable steps to check his competence.

In 2010, Perryman Properties paid over £11,000 in fines and costs under the Construction (Design and Management) Regulations (CDM) after it failed to check the competence of the contractor it had hired on a construction project. In 2009, Richard Atterby, contracted to provide health and safety services to a quarry, was fined under Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations for the “superficial and totally inadequate” risk assessment he had provided, while George Farrar Quarries paid costs and fines of nearly £14,000.

At the quarry, workers were unnecessarily exposed to silica dust; on the construction site a labourer fell through a fragile roof suffering serious back and hand injuries; at Prior Scientific Instruments a paint sprayer was left so ill from exposure to hazardous fumes that he can no longer work. In these examples, two employers had failed to ensure the competence of specialist health and safety advisers, while the property development company had failed to appoint a CDM coordinator to oversee health and safety at the site.

A clutch of UK regulations specify the need for competent people to ensure workplace safety (see Letter of the law, below). But each time we carry out a risk assessment we define requirements for competence. Sometimes this is explicit. An assessment for a demolition project, for example, may specify that a competent person is to carry out an asbestos survey. In other risk assessments, competence is implicit in statements such as “Maintenance staff will make pre-use checks of the ladder and the location before starting a job” or “Electrician will isolate and lock out.” It is unlikely that the maintenance staff or electrician will use written checklists for these actions; they will rely instead on their own competence. But what is competence?

Letter of the law

Regulation 7(1) of the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (MHSW) refers specifically to health and safety competence: “Every employer shall … appoint one or more competent persons to assist him in undertaking the measures he needs to take to comply with the requirements and prohibitions imposed upon him by or under the relevant statutory provisions.”

The Institution of Occupational Safety and Health embodies this need in its Code of Conduct stating that members must “ensure they are competent to undertake proposed work”. The International Institute of Risk and Safety Management’s Code of Ethics includes a similar requirement that members should “only advise on, or undertake tasks, as risk and safety professionals in areas where they are competent and can practise in a prudent and diligent manner.”

Competence is also required by non-health and safety specialists to carry out work safely. MHSW (Regulation 13) requires that young people be supervised by a competent person. It has to be assumed that this supervisor is not intended to be a health and safety specialist, but an experienced colleague who is more aware of the workplace hazards than the young person.

Specific regulations require competence in defined circumstances. The Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations require the use of competent people for inspection and examination of work equipment. Similarly, the Lifting Operations and Lifting Equipment Regulations (LOLER) requires competent people to draw up examination schemes, to thoroughly examine lifting equipment and to plan lifting operations. The LOLER code of practice explains that the differing competences required for each task may need different people; planning is usually carried out in-house, but equipment examinations usually call for external competence. The Fire Safety Order, which consolidated fire safety legislation in 2006, requires the nomination of an adequate number of competent persons to deal with fire management duties.

Towards a definition

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations define someone as competent where they have “sufficient training and experience or knowledge and other qualities to enable him properly to assist in undertaking the measures referred to in paragraph (1)”. (Paragraph (1) refers to the duty to “comply with the requirements and prohibitions imposed upon him by or under the relevant statutory provisions”.)

The Regulations do not define the “other qualities” nor make it clear what Boolean logic is intended by the term “training and experience or knowledge”. Is training vital, but experience or knowledge interchangeable? Or is “knowledge and other qualities” a substitute for training and experience?

The guidance for the Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations (PUWER) includes knowledge, experience and ability in its definition of competence, saying all three are necessary to carry out work safely. Training is not included in the definition, and later in L22 there is some explanation for the omission. Paragraph 181 explains that adequate training will vary, but that in general it should be used to fill the gap between existing competence and required competence — therefore training is not part of competence but merely one means of achieving it.

Pointing out that “a qualification, by itself, is not evidence of competence” the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) Code of Conduct also leaves training out of its definition, suggesting competence is: “a combination of knowledge, skills, experience and recognition of the limits of your capabilities”.

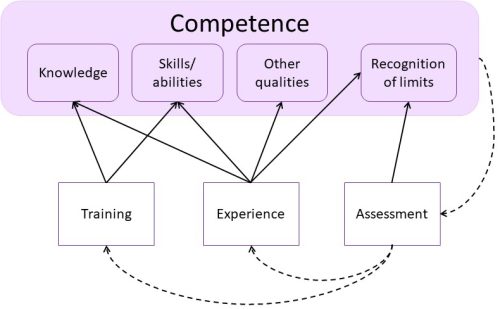

Training may be a suitable method of providing knowledge and skills, but training and experience are the inputs; knowledge and skills (or abilities) are the output. A qualification is evidence of training, not of competence. Two people attending the same training course and given the same opportunities can end up with different levels of competence, because of differences in initial aptitude and competence. Training and experience improve knowledge and skills (and perhaps the “other qualities”). Figure 1 shows this interrelationship as a flow chart, with the mauve shaded area representing “competence” and the white boxes the activities which contribute to competence. Note that recognition of the limitations of competence is itself part of the definition of competence.

The fourth important element in the IOSH code definition is “recognition of the limits of your capabilities.” For health and safety professionals, processes such as continuing professional development, networking with colleagues and reading around the subject provide opportunities to understand what we know — and what we do not know. With non-specialists the limits may be less clear. The case of Ken Woodward, who was blinded as the result of mixing caustic soda and sodium hypochlorite, is an example of where someone did not know the limits of their own competence.

As is often the case, Woodward was trying to be helpful by carrying out a job where his knowledge was incomplete and he lacked the skills to carry out the task safely. In the early days after the Texas fertiliser plant explosion, it is possible to speculate that the volunteer firefighters who died had insufficient knowledge of the behaviour of heated ammonium nitrate.

2021 update

Since writing this article I’ve moved away from the legal definition of competence, as it doesn’t seem to have been very well thought through! More useful for the purposes of identifying training needs, planning how to deliver those needs, and assessing competence, is an academic definition.

In Teaching, training and learning. A practical guide. (6th edition, 2006) Ian Reece and Stephen Walker define competence as “the ability to perform an activity within an occupation.” The health and safety version of this that I use is “the ability to perform an activity, safely and without harm, within the workplace.”

The workplace can be defined as widely as the domain in which your workers operate – so this can include on the road, on customer sites or increasingly, in their own homes.

A little list

So legislation can point us towards some required competences, and risk assessments will suggest many others. More specific guidance is available for some jobs (see box below). But even where such lists are available, risk assessments should be used to identify extra competence requirements. For safety critical processes a more structured and systematic assessment may be needed.

Techniques such as task analysis can be used to describe tasks in sufficient detail to identify all foreseeable consequences of error and any significant hazards in performing the job.

From this description, you can derive a list of skills and experience against which to test people. For example, if the task analysis describes the best way to isolate the power, does the technician follow this method? Do they do the same in an emergency?

In aviation, behavioural markers are defined to assess soft skills such as the ability to communicate, delegate and consult. HSE research report RR086, Competence Assessment for the Hazardous Industries gives some examples: did the captain seek inputs from other members of the crew?; did the captain communicate a decision?

Prescribed compency criteria

The Fire Risk Assessment Competency Council provides detailed “Competency Criteria for Fire Risk Assessors” including being able to “express fire risk for the client in such a manner as to provide at least, a broad comparison of the fire risk at different premises within a single estate of properties”.

Paragraph 95 of L114, the ACoP for PUWER covering the safe use of woodworking machinery, suggests specific competencies expected of a competent user of woodworking machinery, with examples such as “a knowledge of safe methods of working including appropriate selection of jigs, holders, push-sticks”.

The Construction Skills Certification Scheme provides criteria for competence at different levels, for example asking supervisors to explain: “How would you allocate work to team members, taking account of their current circumstances, and briefing them on the quality standards or level expected?”

Meeting needs

Recruitment processes may not require an individual to be completely competent from day one, but should try to screen out those who will not become competent with the resources available in time, support and training. A review of the competences identified for a role will help to identify which can be developed, and which must be present at the time of appointment.

After recruitment, the next step most organisations take to fill the competence gap is training. But competence cannot be assumed as soon as a test has been passed. Further supervised and monitored experience will be needed before the person becomes fully competent, as with a teenager passing their car driving test.

While the MHSW Regulations call for young people to be supervised, this should also apply to any staff carrying out an unfamiliar task. For non-health and safety specialists, if the competences have been clearly defined, the means of achieving them, and the required level of supervision should be straightforward to work out.

Health and safety professionals often need to be more independent in achieving competence. Acquiring knowledge is normally the easy bit.

Imagine you have never before carried out a noise risk assessment. You visit the HSE website and read about the effect of noise on hearing and methods of noise reduction. You read the regulations and ACoP. You talk to the workforce to find out which work areas may have noise concerns. You now have some knowledge.

Then find the noise meter and read the manual. Play with it so you understand all the functions.

Become skilled in its use. But how do you become fully competent to do a noise survey if you have never carried out one, and therefore cannot by definition have the experience to be competent? The IOSH code suggests that competence can be extended either by having your work directly supervised by someone, or at least reviewed by someone who is competent.

The other problem with competence is that it decays. You may be more worried about the driving competence of your ageing father than of your maturing teenager. Some qualifications, such as first aid certificates, require periodic refreshing.

The professional bodies encourage continuing development and refreshing of competence through CPD processes. But many employers could work harder to monitor competence regularly, identify gaps, and provide opportunities to close those gaps. HSE Research Report RR086 describes approaches to fill gaps in hazardous industries, which could be tailored for other organisations.

Other qualities

The IOSH Code of Conduct requires members not only to know their limitations, but to “ensure that they make clients, employers and others who may be affected by their activities aware of their levels of competence.” This goes beyond providing a curriculum vitae and list of previous projects. It requires an honest self-examination and a willingness to say when something is outside your competence.

The case of the Italian seismologists is a case in point. After a series of small tremors, seismologists calculated that there was a small increased risk of an earthquake, with the chance of this being 1:100. This was communicated by the deputy chief of Italy’s civil protection department as meaning there would not be an earthquake. In April 2009, earthquakes hit L’Aquila in central Italy, and 309 people were killed. Six seismologists and a government official were prosecuted for manslaughter, and sentenced to six years in prison.

The prosecution succeeded not because the seismologists had failed to predict the earthquake, but because they failed to communicate their estimate of the risk.

For health and safety professionals perhaps the message here is that there is no point hiding your advice about hazards and controls in a risk assessment and saying “told you so” when an accident happens; competence means we have to know how to get the advice out there, used and working.

Tim Briggs, senior lecturer in health and safety at Leeds Metropolitan University, suggests that competence therefore needs a much broader definition.

“Competence involves more than knowledge and skills,” Briggs notes. “Competence involves many soft skills such as influencing, negotiating, critical thinking, analytical skills, customer orientation, problem solving skills, leadership skills and communication skills. Not all these skills can be taught, but they can all be learned.”

Perhaps these are the “other qualities” alluded to in the MHSW definition.

E-learning systems allow users to print certificates showing they have passed 70% of the multi-choice questions. Elsewhere, we hold training sessions, and issue certificates to those who stayed awake throughout the presentation. We have trained our users.

But, if we have not considered competence at the recruitment stage, we may have untrainable staff. Unless we have a systematic approach for identifying required competence, measuring existing competence and describing the gap, training will not achieve its aim.

And unless competence is assessed in the workplace under all conditions, there is no evidence that the training has actually worked.

While such approaches are most frequently used for non-specialists, it would be a worthwhile challenge to come up with competency requirements for ourselves as health and safety practitioners.