Evidence based: Generations X, Y and Z

Generations?

Table 1 shows a popular scheme for classifying people based on their date of birth.

Most of the stereotypes about generations are unhelpful: baby boomers are diligent but selfish; generation X are loyal to their employers, but cynical; millennials are inherently sociable and yet technology-obsessed. In reality, each generation has its share of generosity and selfishness, of introverts and extroverts, of risk-takers and risk-avoiders.

In the USA, David Costanza, Associate Professor of Industrial-Organizational Psychology at George Washington University and Senior Fellow at the US Army Research Institute in Washington DC has been researching generational differences since 2010. He carried out a systematic review of 18 studies on generational differences in work-related attitudes, job satisfaction and organisational commitment. In Generational differences in work-related attitudes: a meta-analysis Costanza concludes that:

“meaningful differences among generations probably do not exist on work-related variables like job satisfaction and organizational commitment.”

Where studies have found differences Costanza believes these can be explained by age, career stage or economic conditions, or the findings are based on “serious statistical and methodological flaws.” He concludes:

“organisations should not be wasting time and resources on interventions addressing generational differences that don’t exist.”

Table 1: Popular generational labelling

| Birth years | Generation label |

|---|---|

| 1946 to 1964 | Baby boomers |

| 1965 to 1979 | Generation X |

| 1980 to 1995 | Generation Y or Millennials |

| 1996 to 2012 | Gen Z or post-millennials |

| 2013 to 2025 | Generation alpha |

Why does it matter?

Regulation 19 of the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations place a particular obligation on employers to consider the needs of young people, to protect them from “any risks to their health or safety which are a consequence of their lack of experience, or absence of awareness of existing or potential risks or the fact that young persons have not yet fully matured.”

While elsewhere the regulations define a young person as someone under 18, any parent of an 18-25 year old can tell you that nothing magical happens at 18 to mean they are suddenly safer. Someone starting their first job aged 22 after university might have less work experience than a 17-year old. HSE statistics show that 20-24-year olds have a higher accident rate than those 19 and under, and that people of any age are more vulnerable to accidents in their first six months than at any other time in their employment. What we label as “common sense” is based on experience and training. Not running with tools, picking up rubbish, checking a ladder before you climb, all have to be habits that we learn – often undoing habits from school and home.

Those providing this experience and training are usually older. If we believe the stereotypes, barriers between people can be built, making it difficult to communicate about what matters. If we take a sledge-hammer approach to training, assuming that all young people will love eLearning, and all the older workforce will prefer classroom training, for example, we won’t be getting the best from our training tools, or from our people.

Young workers over 18 still need training

So we're all the same?

If we drop the stereotypes, there are some shared experiences within each age group that might have an impact on attitudes to work, towards health and safety measures, and to how people expect to be trained. We will look at those areas where it might be safe to generalise about the experience of the different generations (while remaining cautious about making assumptions for individuals).

Education

Schooling has changed, so how people expect to learn in the workplace has changed - but everyone can benefit

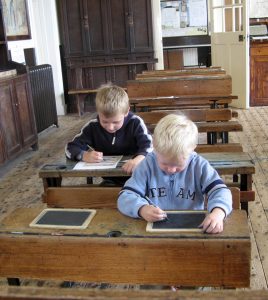

Many people who provide training now went to school at a time where the teacher was the source of knowledge. The knowledge was written on a blackboard for children to copy into their exercise books, so they could be tested on their recall of that knowledge.

In contrast, those starting school in the 2000s were taught using active, participative methods. They were expected to research facts for themselves. They watched YouTube videos for homework. Instead of essays, they made papier-mâché models of cells for biology and videos about climate change for geography. Instead of the teacher setting tests, they designed their own on Quizlet, and tested each other.

Young people might therefore be uncomfortable if expected to sit in a classroom while someone reads out a PowerPoint presentation on site rules and fire safety to them. If their supervisor delivers a tool box talk in a monotone and then asks “have you got that?” it is unlikely they will understand what needs to be done.

‘Milestones and Millenials’, published by the Mayo Clinic (Desy et al, 2017) describes research into how medical students prefer to learn, which could have relevance for safety professionals. It describes those born after 1982 as “demanding educational consumers” rather than passive recipients.

This doesn’t mean that young people will thrive with eLearning. It might work for some people, but most eLearning is still designed with a “here are the facts – have you got that?” approach.

Approaches to helping young people to understand safety are likely to be more successful if they are student-led, not authority-led, using active methods, and where appropriate, making use of technology and social media. Allowing them to work in teams to discover knowledge, and apply it to their own problems will be a more valuable experience.

The LOcHER project (Learning Occupational Health by Experiencing Risks) has taken this on-board. The LOcHER project (or “learning about occupational health by experiencing risks”) has taken these ideas on board. With a steering group that includes the HSE, RoSPA, and Safety Groups UK, LOcHER aims to encourage a positive attitude towards health and safety culture among further education students and apprentices. The idea is that experiencing a task in a safe way should help students to embed knowledge in their long-term memory and influence longer-term positive attitudes and behaviours.

Blackpool and the Fylde College was one of the first colleges to get involved in LOcHER, and Joanne Shepherd was enthusiastic from the start. Although backed by the HSE and supported by the Safety Groups UK and industry specialists, Shepherd explains that LOcHER was developed by the students. “They come in from school already aware of the importance of safety, and LOcHER gives them the opportunity to find out more about health issues at work. By researching it themselves, and deciding on their own outputs, they remember the facts – and believe the results.”

Social media is important here in the outputs that the students decide on. Videos are popular “you can’t imagine someone sharing an essay about respiratory protection on Instagram” remarks Shepherd. By contrast, the Dust n Boots rap on YouTube has had over 2000 hits across two postings. Other outputs from the project have included comic book strips to describe cyber security dangers, and a lighting installation from Creative Arts students to alert people to safety issues in a work space.

Dust n Boots rap from the LOcHER project

Technology

Age is not a barrier to technology adoption

Office of National Statistics (ONS) surveys show that the younger generation are more likely to own a phone, and more likely to use it on-the-go for internet access. The difference in how the generations have been educated is reflected in how people use the internet. Those who have grown up with computers are more likely to post pictures and videos on the internet, while the older generations are more likely to use it as a tool to do familiar tasks more easily, like banking, booking accommodation or transport, and shopping. Critically, many younger people see it as the prime means of communicating with people. When I’ve suggested to my late 1990s son that he might pick up the phone when he doesn’t get a reply to an instant message, I might just as well suggest he use a fax machine.

Joanne Shepherd’s experience of the students coming through courses at Blackpool and The Fylde College matches the statistics. “Given a choice” she notes “between a pen and a laptop, they will always choose the laptop.”

On technology, ‘Milestones and Millenials’ (Desy et al, 2017) found that medical students value “the incorporation of technology into the workplace” but and expect technology within their education. However, not all technology is appropriate. Desy et al found that one of the top five cited learning preferences was “working together in groups.”

Safety culture

For those who took O levels or CSEs at school, safety was pretty much limited to how to hold scissors when walking, and not running in the corridor. Safety was more important for those at school around the turn of the century, with rules learned about how to check Bunsen burners. But, as Shepherd explains “as a school lab technician in 2002, I could see the staff were conscious of the need to keep the children safe, but children were given rules to follow, but not to understand.” Shepherd has seen a change “Now they learn to interpret risk assessments, and for some science courses they have to produce their own risk assessment.”

The AQA Criteria for the assessment of practical competency in A-level Biology, Chemistry and Physics includes the ability to Identify hazards and assess risks “making safety adjustments as necessary” and the ability to “minimise risks with minimal prompting.” The current generation have learnt to assess risk rather than follow rules.

School safety is not just about risk assessments however. School trips provide further opportunities for children to learn about risk. Venues such as Danger Point in Flintshire and Hazard Alley in Milton Keynes provide opportunities to introduce children to everyday risks in a safe, fun environment. Jo Green, Director of Safety Centre Ltd which runs Hazard Alley explains how their young visitors are “encouraged to assess an everyday situation such as a kitchen or living room, railway crossing or street and suggest ways of making them safer.” The children learn not from rules or pictures, but in environments with trailing flexes and simulated traffic. Jo Green reports that the children who visit “leave with confidence and greater skills in identifying hazards and managing risk.”

The Council for Learning Outside the Classroom is a further initiative to encourage active learning about risk.

Children learning early about the hazards of a construction site at Hazard Alley in Milton Keynes. Don't expect them to read bullet points ten years later when they join the workforce

My visit to Hazard Alley

In preparing for this article I was made welcome at Hazard Alley in Milton Keynes. As well as meeting the Director, Jo Green, volunteer guide Peter Ballad shared his experience of excited children visiting.

From the first children arriving at Milton Keynes’ Hazard Alley in 1994 to school trips today, Peter believes they have always been enthusiastic about its theatrical experience – Peter described the “wow factor, when the curtain is pulled back to reveal hazard alley.”

Milton Keynes was the first centre to open, but there are others as members of the Safety Centre Alliance, formed in 2005 to support existing centres and help create new ones.

The Milton Keynes centre relies on 1990s technology: video projections, a few interactive touchscreens, and even a payphone where children have to make a 999 call to rescue “grandad” from a house fire. Peter Ballard is sceptical about introducing more technology to the experience, though. “One of the other centres tried to rely on more technology, but it wasn’t as immersive as standing in what feels like a real street, or next to a railway tunnel listening to what sounds like a real train,” he says. Although today’s generation might be more comfortable with technology than earlier generations, they are not, it seems, bored by make-believe scenes as an approach to learning.

Hazard Alley also offers a form of experiential learning that I would love to offer in workplace training. After a talk about smoke detectors and what to do if there is a fire at home, fake smoke appears underneath a door. Younger children are encouraged to leave at this point, while older ones might be left without an adult for a few moments – invariably, they follow instructions and get out of the house, shutting the door behind them. This is the point where they stand outside the house and see “grandad” at the window. When I have suggested using fake smoke for fire drills, I have been talked down!

But one change that Hazard Alley has noticed over the years is in funding provision. In the past, local education authorities and even the Home Office have paid the costs for schools to visit, making it effectively free to use. Now that academy schools control their own funding, teachers have to make an internal case to pay a fee per child to visit the centre, plus transport costs.

Hazard Alley is trying to help teachers build the business case for coming by providing handouts on how a visit can fit in with the National Curriculum.

On my visit, the centre’s director, Jo Green, mentions her delight when meeting adults who had been to the centre when they were small children: 15 to 20 years later, they still remember making the 999 call. In at least one case she knows of, a child who learnt that skill on a school trip was able to apply their knowledge when there was a real fire in the family home.

However, the experience of the centre bears out David Costanza’s suggestion that the “generations” aren’t all that different: children in 2018 and children in 1994, it seems, are equally as happy to learn about safety by playing make believe in a sociable environment.

Safety culture

Let’s look at those ‘generation’ dates again. Then think about what might have influenced people at the point they were starting work and getting established. The scars from the tragedy at Aberfan will never heal for those lived through it, and the need to find rules to prevent such accidents prevails. System failures in the 1980s illustrated that a rule set might not be sufficient – rules interacted in complex ways, and a system approach was needed. The six-pack of regulations from the EU arrived in 1992, with support for a risk assessment approach. The 1997 Labour government saw the UK at last join the Social Chapter, with restrictions in working hours and the introduction of a minimum wage. These introduced the idea that people were entitled to more than simple protection from physical harm.

Table 2: What has influenced each age group's attitude to safety?

| Birth years | Generation label | Education | Safety regime influences |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 to 1964 | Baby boomers | Educated by chalk and talk (backed up with slipper and cane) | 1966: Aberfan 1974: HSW Act |

| 1965 to 1979 | Generation X | Mostly chalk and talk, but “progressive” education emerging | 1986-88 Chernobyl, Herald of Free Enterprise, Kings Cross, Piper Alpha. System disasters. 1992 Six pack, including Management of Health and Safety at Work regulations: safety by risk assessment |

| 1980 to 1995 | Generation Y or Millennials | Active learning, often supported by teachers using technology | 1997 Social Chapter 1998 Working Time Directive 2005 Texas City and Buncefield explosions show that safety can’t be assumed because of a lack of accidents. |

| 1996 to 2012 | Gen Z or post-millennials | Emphasis on finding out for yourself, putting the technology in their hands | Changes brought about by BREXIT. Rise of unpredictable terrorist attacks in European cities – perhaps you can’t control risk; ‘YOLO’ |

How knowing this helps

Although every generation has its technophobes and technophiles, you are likely to find that most young people are comfortable with the use of technology. Your existing staff might be resistant to moving from paper checklists to tablet-based audits, from classroom to eLearning, from text-based method statements to video-based tutorials, or from Excel spreadsheets to an online safety management system. They might not be keen to work with cobots (collaborative robots) or to use wearable technology. If you want to introduce new technology take advantage of the greater acceptance of technology amongst young people to pilot any new technology – but don’t assume they’ll all like it, and remember their expectation of leading their own learning, not being spoon-fed.

Using their enthusiasm and their initial willingness to assess risk and make suggestions could also be a good way of encouraging worker participation in the organisation. Safety managers could deploy Quizlet for an induction rather than deliver a one-way talk where the only question is “got that?”, or staff could make up their own quizzes, to test each other’s knowledge and understanding.

While many of the older generation are turning their thoughts to new approaches to safety, away from compliance-driver, rule-based approaches, to worker-centred “safety differently”, for the younger workforce the “new” ideas map to how they were educated. As well as considering how to keep them safe at work, we should therefore look at them as future health and safety professionals.

Other approaches

It shouldn’t all be about technology though. For example, the sort of listener fatigue that anyone can suffer from during a toolbox talk or other pre-job briefing can be overcome using participative methods. For example, why not have a quiz rather than deliver a one-way talk where the only question is “got that?” Where teams include young and old, the enthusiasm of the young people to answer questions could be infectious, and perhaps you could give them time to make up their own quizzes, to test each other’s knowledge and understanding.

Health

The evidence on millennial attitudes to health is mixed. Many sources claim millennials are more conscious of health issues, healthy eating, exercise; and yet NHS statistics suggest that those born since 1980 are more likely than previous generations to be obese, and the picture is even worse with those born from 2000 onwards.

Mental health is increasingly on the agenda across the entire workforce, but practitioners agree that there are particular issues with

younger people. Ray Roberts, head of mental health at Transport for London (TfL) explain at the Health in Construction Summit in 2018 that TfL was paying

particular attention to the mental health of the apprentices and trainees in its workforce, considering young adults to be particularly vulnerable. Young adults, he pointed out, can be particularly vulnerable to anxiety and depression due to concerns about their education, finding the right partner, money and debt, leaving the family home, and increased exposure to drink and drug cultures.

Joe Dromey, a senior research fellow at the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), explains that IPPR research in 2017 found “a significant increase in the reported incidence of mental health problems among younger generations. 16% of young people (aged 16-32) experienced mental health problems in 2014, up from 13% a decade earlier,” he says.

Christine Husbands is managing director of RedArc Nurses, which provides nursing and occupational health support to employers. Christine says that the incidences of mental ill-health requiring support dealt with by RedArc nurses are skewed towards younger workers. Along with the types of pressure identified by Roberts, she feels that the flip side of being a “digital native” is the pressure to present a perfect life on social media. On the other hand, a more positive manifestation of the “sharing” culture is the fact that “they’ve grown up in an environment where it’s OK to talk about personal issues.”

In her experience, though, when younger people encounter mental health difficulties, they present more of a challenge than older generations who face similar problems. “They can find it difficult to get themselves into a place where they’re able to go back to work. Older people are more sanguine and can say ‘I’ve done this before’.

But employers who engage with the challenge can expect to reap longer term benefits. “You avoid building up a problem that manifests itself in a worse way.”

Social media also defines younger millennials’ preferred interventions, Husbands says. “Youngsters are more familiar with using technology, so they expect technical solutions. It’s not about going to a therapist’s office; they’re used to getting things immediately, they look for things that are quick and easy and private.

Technological solutions make it easier for people to engage,” she says, describing a new app that RedArc is delivering that will offer self-management tips on mental health, or link users to counselling services.

Conclusions

While in the 1970s, “talking back” earned a slippering or at least a detention, 21st Century teachers congratulate students when they find out something the teacher doesn’t know. Working with a compliance-based approach, under a “don’t ask questions” rule-set might be difficult for young people joining the workforce now. Many will naturally question and challenge. If not handled well, these challenges could be supressed, so that the enthusiasm is switched off, and like everyone else, they will get on with their work. However, using their enthusiasm and their initial willingness to assess risk and make suggestions could be a good way of encouraging worker participation in the organisation. While young people might be the drivers of more participative methods of training and of work participation, it is likely that such approaches will be more successful for people of any generation.

From what Shepherd has seen of the young people coming through her college, we can be positive “The future of HS is in very safe hands” she says.

Further reading

I have a shorter article on this topic on the IOSH Magazine website, as part of the Lexicon series.