For and against: hearing protection

First published in Health and Safety at Work Magazine, November 2018. Links and references to statistics were checked and where necessary updated in December 2023.

The problem of work-induced hearing loss

A study of the effectiveness of noise regulations in the US (Daniell, Swan et al, 2006, Journal Occupational and Environmental Medicine) found poor compliance, high levels of noise exposure and concluded that the results “raise serious concerns about the adequacy of prevention, regulation, and enforcement strategies in the United States”.

Are we any better in the UK? One measure of success is from the Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit scheme (IIDB). The IIDB registers only extreme examples, where someone’s hearing is damaged severely enough to count as disabling. HSE figures show that, before 2005, more than 300 people a year were classified as deaf under the scheme. Between 2006 and 2010 the total hovered around 200 new cases a year. Figures flattened at around 120 per year from 2012 to 2014, and then continued to drop, staying below 100 new cases a year since 2016. But it is difficult to say whether this is due to improved noise controls or changes in the nature of work.

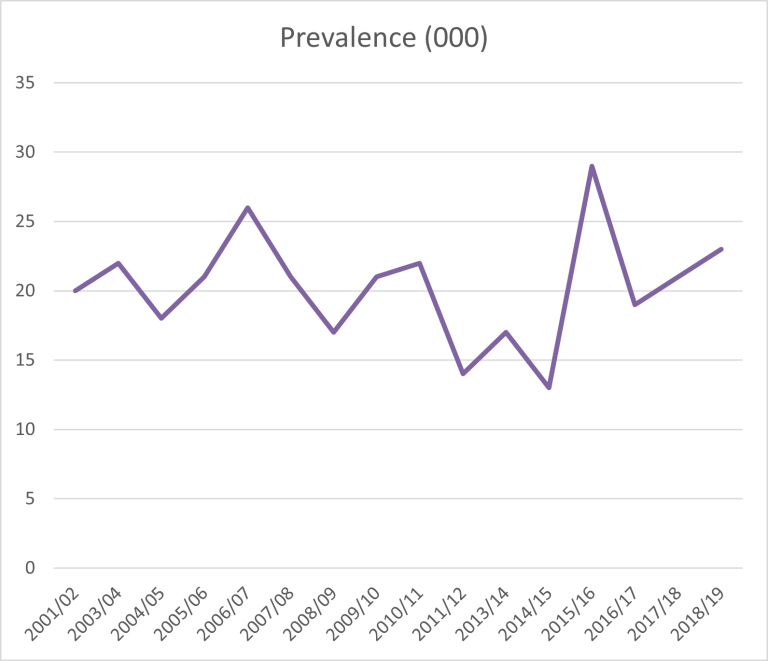

The quarterly Labour Force Survey provides a more mixed picture. It shows a prevalence peak in 2006–07 when an estimated 26,000 people suffered from “hearing problems” caused by work. This peak might have been due to a heightened awareness when the Control of Noise at Work Regulations were introduced. But the figures haven’t shown any dramatic downward trend over the longer term. The central estimate for prevalence has bobbed between 13,000 people (in 2014/15) and 29,000 in 2015/16, with the latest reliable figures for 2018/19 showing 23,000 (see graph).

Hearing prevalence central estimate 2001 tp 2018 from LFS

Research

A report by the Medical Research Council and the Institute of Sound and Vibration Research for the HSE (RR669) reviewed evidence for the effectiveness of noise at work regulations. The authors admit they made no attempt to discriminate between the effect of the Noise at Work Regulations 1989 and the Control of Noise at Work Regulations 2005. They seem reluctant to state that the regulations are ineffective, but they admit that compliance with the regulations had no impact on either occupational noise exposure or in employee hearing ability.

Action levels

Peter Wilson, director of the Industrial Noise and Vibration Centre (INVC), identifies one problem with noise law as the focus on the action and limit values, in particular on the upper exposure action value of 85dB(A). At or above 85dB(A) the employer must “reduce exposure to as low a level as is reasonably practicable by establishing and implementing a programme of organisational and technical measures” and, if there is no other practicable means, provide hearing protection.

If the noise can be reduced below 85dB(A) the burden on the employer is reduced. So when offered the opportunity to invest in low cost engineering measures that could reduce noise levels from 98dB(A) to 91dB(A) Wilson reports “some organisations are not interested. They think the investment is not justifiable unless they can reduce the noise to 85dB(A) and get rid of hearing protection”. According to Wilson, this approach misses opportunities for cost and productivity savings that the engineering measures often bring. Hearing protection is also less effective at noise levels above 95dB(A), he adds.

The HSE guidance of the regulations, L108 tries to offset the emphasis of the legislation on the action and limit values by reminding the reader of the more general requirement in Regulation 6 that, if the risk from exposure to noise cannot be eliminated, it must be reduced to as low a level as is reasonably practicable.

Meeting Action Levels isn't enough if it is reasonably practicable to reduce noise further

Evidence of interventions

A 2012 Cochrane review by Finnish occupational health academic Jos H Verbeek and colleagues set out to assess the evidence for Interventions to prevent occupational noise-induced hearing loss.

Following the hierarchy (see right), they looked first for evidence of studies of the success of engineering controls: means of reducing or eliminating sources of noise, changing materials, processes or workplace layout. They found none. Instead, they found 16 studies that evaluated the effects of hearing loss prevention programmes (HLPPs) and a further eight focusing on the value of personal hearing protection. They reported that the quality of studies was “low to very low”.

Hierarchy of noise control

Controls to prevent noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) form a well-known hierarchy, based on Schedule 1 of the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations and the Control of Noise at Work Regulations (CNW). Examples are given in part 3 of L108.

- Eliminate the hazard by doing the work in a different way, eliminating or minimising exposure to noise.

- Modify the work, process or machine to reduce noise emissions.

- Replace the tools and equipment used with lower noise alternatives.

- Arrange the workplace and workflow to separate people from the noise.

- Reduce the noise reaching people by controlling it on its path from the source.

There is some overlap: using quieter tools as suggested in point 3 is an example of doing the work differently. Personal hearing protection: ear muffs and ear plugs, can be considered as part of point 5, reducing the noise reaching people by controlling its path, along with collective measures such as silencers and insulation.

Anecdotes

The HSE website includes case studies of noise control, helpfully grouped by noise control technique. It gives examples of organisations that have reduced noise exposure through substitution, maintenance, design, isolation, insulation and damping.

Though these case studies would never reach the randomised control trial criteria for a Cochrane review, they do show that organisations can make engineering noise controls work, in some cases reducing levels from above 90dB(A) to 85dB(A) or below, removing the need to enforce hearing protection.

Buy quiet

You wouldn’t buy machinery without appropriate guarding, or vehicles with unreliable brakes, so why buy equipment that is noisier than it needs to be? Employers are responsible under under Regulation 6(3) of the Control of Noise at Work Regulations for the “choice of appropriate work equipment emitting the least possible noise” and to “the design and layout of workplaces.”

You might think there should be some onus on the manufacturer. Manufacturers and suppliers have a duty to control noise levels from some types of work equipment under the Supply of Machinery (Safety) Regulations (SMR) and in some cases under the Noise Emission in the Environment by Equipment for Use Outdoors Regulations. Schedule 2, Annex 1 of SMR states:

“Machinery must be designed and constructed in such a way that risks resulting from the emission of airborne noise are reduced to the lowest level, taking account of technical progress and the availability of means of reducing noise, in particular at source.”

Both regulations also require manufacturers and suppliers to provide customers with information about the expected noise levels of their equipment. But in 2013 an HSE-funded survey of noise emission and risk information supplied with a range of work machinery found 82% of the machine instruction sets reviewed contained inadequate information about noise emissions. Another HSE-funded report RR625 (2008) looked at noise emissions from specific tools, finging that noise emissions could be 15dB higher than stated, depending on how the tools were used.

So has the HSE been busy prosecuting manufacturers and suppliers? In 2018 I found three SMR prosecutions on the HSE database – all related to failures in guarding which led to serious injuries to their customers’ employees. There were 16 notices on the improvement and prohibition notice database. These relate to subjects such as the lack of a technical file or to failures in mechanical, chemical or gas safety; none has been issued to encourage manufacturers to reduce noise risks “to the lowest level … at source”.

Checking prosecutions and notices under SMR in 2023 nothing has changed, although there are still plenty of improvement notices telling employers to protect their employees’ hearing against noisy equipment.

Peter Wilson, director of the Industrial Noise and Vibration Centre, agrees that the HSE does not have an effective way of enforcing SMR: “Only the clients are in a position to police the manufacturers and suppliers. Clients should specify and enforce in-situ noise limits as part of the contract. If the machinery doesn’t match the supplier’s promises on installation, clients shouldn’t pay.”

The HSE have advice on quieter buying to get you started.

Cover your ears

If we “buy quiet” and consider all the engineering, workplace layout and job design issues but still have residual noise levels that require personal hearing protection, will it do any good — and will people wear it? Of the 16 HLPPs reported by Verbeek (2012) none showed any significant reduction in hearing loss for those who were part of the programme when compared with controls.

Timescales for follow-up measurements were between three and 16 years, which should have been long enough to detect some effect. The best Verbeek could offer was that there might be a “possible preventive effect on hearing loss when using personal noise exposure monitoring and worker feedback”.

There was only very low quality evidence that use of hearing protection as part of an HLPP decreased the risk of hearing loss. Verbeek concluded that the effectiveness of ear plugs “depended almost completely on proper instruction of insertion” and “noise attenuation ratings … under field conditions were consistently lower than the ratings provided by the manufacturers”.

Research by the HSL published in 2009 as RR720 “Real world use and performance of hearing protection” confirmed the finding that the manufacturer’s data could not be relied on. HSL carried out laboratory tests on a range of earplugs and ear muffs, finding that under ideal usage conditions the single number rating (SNR) — the measure of noise reduction used for ear protection — was on average 5.5dB less than the manufacturer’s stated value. When product age, temperature and use with other PPE such as goggles and hats was included, the SNR of ear muffs could fall 10dB below the stated level. Some manufacturers blamed the poor results on badly fitting ear protection and now offer fit testing services.

Promoting hearing protection

A Cochrane review carried out by Dr Regina El Dib and colleagues in 2012 looked specifically at interventions to promote the wearing of hearing protection. Their report opens with a useful statistic for workplace promotional campaigns in which staff claim to use hearing protection “most of the time”. El Dib et al cite evidence that “wearing hearing protection for only 90% of the time will decrease effectiveness to less than one-third”. They conclude that simply providing people with hearing protection is not enough to encourage its use, and make recommendations on how to improve promotional campaigns.

As well as providing multiple options for hearing protection, they suggest that programmes need to be tailored to each individual’s risk perception and attitude towards hearing protection. Risk awareness could be improved by involving staff in noise assessments and audiometric testing, but El Dib’s study found that off the shelf training videos produced little or no benefit.

Brown teaches the IoA course on workplace noise risk assessment and attempts to scare people into compliance. “I play them a soundtrack of my son talking when he was very young,” he says. “Then I play a processed version of the track, as it would sound with damaged hearing. I paint a future where they will have no relationship with their grandchildren because children don’t have much patience, and will assume grandad is ignoring them if they don’t get a response.”

El Dib’s message is that, although tailored and repeated interventions will convince some people to wear HP some of the time, it will be difficult to convince all of the people who need it to wear it all of the time.

Brown had to disappoint one safety manager who thought everyone was wearing hearing protection because she could see the yellow plugs in their ears. “I pointed out people were wearing them sideways, providing almost no protection.” The field observations reported in RR720 support this, finding that, even in organisations that have volunteered for the study, and even when being observed, only 60% of workers who were supposed to wear hearing protection were protected, either because they didn’t wear protection at all or because they wore it incorrectly.

Risk homeostasis

As a caution, a study of noise in American mines looked at noise levels and controls before and after the implementation of the Mine Safety Health Administration 1999 regulations on noise exposure (from 1987 to 2004).

The authors of the study published in 2007 in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene reported that noise levels above and below ground had been reduced, and use of hearing protection improved — but that in many cases shift lengths were increased, so overall noise exposure remained the same for many workers.

Most of the research into the effectiveness of hearing protection is from the US. The 2013 update of the El Dib review was withdrawn, and the Cochrane ear, nose and throat disorders group states there will be no further updates since this is no longer a priority area. It has presumably caught up with the idea that there is more evidence in favour of eliminating and reducing noise at source than in the benefits of ear protection.

The weight of evidence is that even the best campaigns, educational programmes and feedback processes still leave workers in noisy environments with damaged hearing compared with those in quieter settings. The solution is to eliminate or reduce the noise, not teach people to protect against it.

Gordon Brown is not optimistic, however: “Virtually every assessment I have done contains recommendations for noise control at source, but at follow up visits I usually find it hasn’t been done. Some organisations have reached the erroneous conclusion that it is cheaper to pay the occasional claim than to engineer noise out of the workplace.”

Emma Shanks, a noise and vibration research scientist at the Health and Safety Laboratory and author of RR625, concludes: “Buy quiet is a long term strategy that dutyholders can use that works towards a working environment where no hearing protection is required, although short term, interim hearing

protection use might be necessary.”