Chapter 4: Identify the hazards - include all the right people

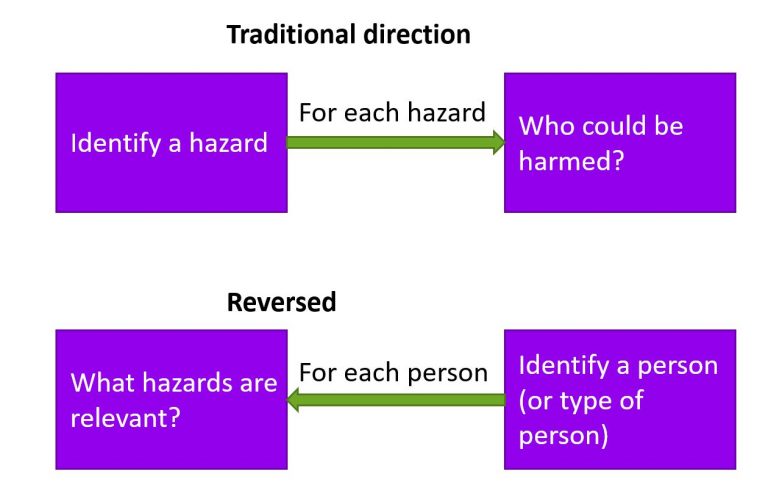

4.1 Two directions

There are two directions to approach this problem from. In section 4.2 we take the first approach: continue to think of hazards first, and then who could be harmed, but do so more thoroughly. In section 4.3 I’ll look at the problem in reverse: start with the people, and then consider the hazards. In reality, you might need to go back and forwards between hazards and people (and assessment and controls) before you are confident that you’ve identified all reasonably foreseeable hazards and their impacts.

4.2 Identify who could be harmed for each hazard, but do it better

As we’ve already highlighted, something that is not a hazard for one person, might be to another. A child might be more likely to be scalded carrying a hot drink, but less likely to break a hip when falling down a short flight of stairs.

Table 4.1 suggests some types of people who might be vulnerable for typical hazards. I’m not giving a tutorial here on radiation or hazardous substances, or any other hazard. If your staff might be exposed to any significant or complex hazard you need to understand it in a lot more detail than this book provides. The intention of Table 4.1 is to illustrate how you could identify which people might be especially impacted by hazards in your organisation. Reasonable adjustments or additional precautions might be sufficient in some cases, so this table is not a list of people to ban from certain tasks.

| Hazard | Who could be (more) harmed? |

|---|---|

| Substances Hazardous to Health (chemical, biological and physical) | Check safety datasheets, but consider: • People with asthma and other respiratory conditions • People with dermatitis and other skin conditions • Expectant or breastfeeding mothers and their children. |

| Ionising and non-ionising radiation | Expectant or breastfeeding mothers and their children. Young people who are still growing. People with pacemakers. |

| Vibration | People with pre-existing Hand Arm Vibration Syndrome (HAVS), Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) or primary Reynaud’s disease. People with pre-existing symptoms even if not diagnosed, or with poor circulation. Smokers take longer to recover from vibration-induced symptoms. Prolonged exposure to vibration during pregnancy can increase the risk of miscarriage, premature birth or low birth weight. |

| Noise | People with existing hearing loss or tinnitus. People with some mental health conditions might be more prone to anxiety in noisy environments, well below exposure limits. Prolonged exposure to excessive noise can increase blood pressure which can be dangerous during pregnancy. |

| Handling heavy loads | People with pre-existing musculoskeletal conditions, or other health conditions, or recent surgery. People who are stressed and smokers Hormones present during pregnancy and breastfeeding can make muscle injuries more likely. |

| Temperature extremes | A breastfeeding mother can be more prone to dehydration. Heat stress or heat exhaustion could be more harmful when pregnant. Women near or during the menopause might need more control over the temperature and ventilation of their working environment. Some one with vibration-related or circulatory conditions can be more prone to suffer in the cold. |

Table 4.1: How some people are especially vulnerable to some hazards

When creating your own version of Table 4.1 you need to consider individual members of staff, and ‘people in general’ who will be more susceptible to each identified hazard.

For the hazard of fire, we’re already familiar with this idea. Organisations commonly use personal emergency evacuation plans (PEEPs) to plan how responsibilities for disabled individuals will be met. Organisations that are open to the public, such as shopping centres or places of entertainment can’t have a PEEP for every individual who might visit, so they will usually create general emergency evacuation plans (GEEPs) for the most common types of disability. For example, covering limited mobility, hearing impaired, sight impaired and learning difficulties. These are based on a risk assessment of the hazards that a person of each type might be exposed, and the controls that might be appropriate.

Ask yourself: PEEPs and GEEPs are now commonplace as part of fire safety plans. But what other hazards could you apply this approach to in your workplace?

For example, rather than starting from scratch with a DSE assessment every time someone with a back condition needs adjustments to their computer workstation, could you write a “generic DSE assessment for back problems” that could be modified. What about a “generic work at height assessment for people with health conditions” that considered what medication, illnesses or disabilities could impact safety when working at height?

A last thought on the “do it in order, but do it better” approach is to consider, explicitly, both collective and individual hazards:

- Collective hazards, such as a fire, can harm anyone near the location of the hazard, which could include members of the public and unexpected visitors.

- Individual hazards are focussed on a narrow audience of people. Only someone holding a vibrating tool can be exposed to hand-arm vibration from that tool; only the worker with her hand near the moving blade risks losing her fingers.

Ask yourself: When the facilities company considered the cleaner vacuuming the stairs, was that an individual or a collective hazard? What was the hazard to the client staff?

The hazard of electrocution (for example) was an individual one for the cleaner. But the hazard of a trailing cable was a collective one, as anyone using the stairs would be exposed to that. Looking for the collective, as well as the individual hazards, might have been a sufficient reminder to the facilities company to consider hazards to the client staff.

4.3 Reverse the process

Instead of starting with the hazard, in some cases, it can be useful to start with the people who might be harmed. This is not so strange as you might think.

Ask yourself:

In the previous section I said that PEEPs and GEEPs were used for the hazard of fire. Is that completely true? What other hazards might be identified in an emergency evacuation plan?

While fire might be the hazard with the greatest consequence, the risk assessment behind an emergency evacuation plan starts with the person who might be harmed, and identifies many hazards other than fire. For example, moving people in an evacuation chair can cause problems, both to the evacuee and to those handling the chair. One way to reduce the risk is therefore to ask a person with mobility limitations to wait in a temporary refuge during the first stage of an evacuation. If there has been a false alarm, or the process is a drill, there is no need to risk moving a disabled person down the stairs unnecessarily. If you have ever waited in a temporary refuge you might be aware of another hazard this exposes people to. Noise. Refuges tend to be in stairwells, right next to a fire alarm sounder. The noise is, quite literally, deafening. The carefully documented procedure relies on the disabled person, or their buddy (a person appointed to accompany them), to communicate with the evacuation co‑ordinator using an intercom provided. In practice, you discover that any communication over the sound of the fire alarm is impossible. What hazards might that lead to? It could expose rescuers, buddies and disabled to fire, but it could also lead to the evacuees deciding to go down the stairs away from the noise.

With a PEEP, the process of focussing on the person first, and considering the hazards they face can be very effective. But the same organisations then ignore disabled people in relation to every other risk assessment in the organisation. It seems odd to ignore vulnerable people for the majority of the time, and then suddenly remember them when the fire alarm sounds. One organisation I worked with did have a process in place for considering the different abilities of each trained volunteer in relation to using some hazardous equipment (such as steamers and tagging guns), carrying out banking tasks, and using a ladder. However, few of the managers understood the process, and I saw assessment after assessment that included no comment that an 85-year old with severe arthritis should not climb a ladder, or that a 14-year old shouldn’t be asked to deliver large sums of cash to the bank. No one had ever explained to the managers that one purpose of the individual assessment was to identify hazards particular to each volunteer.

Individuals and groups

Providing a separate risk assessment for every individual, as well as premises and equipment risk assessments might be practical for a small organisation, but for a larger organisation, a different approach is likely to be more effective.

When people responsible for fire safety prepare GEEPs (as opposed to PEEPs), they consider types of disabilities people might have, and how this would impact their ability to evacuate. I had a great friend who had started to lose his sight as a teenager. He never learned to drive, and walked everywhere. He did karate. He was tall, strong and heavy. He regaled me with stories of turning up at airports on his own, having pre-booked support, and being met by diminutive members of staff with wheelchairs to get him from lounge to airplane. Sometimes the staff member would insist on struggling to push this large, very fit young man in the chair; other times, they had the sense to listen to Alex explain that he just needed a guide to walk ahead, and let him touch their arm.

The problem raised by Alex’s experience was the overly generic measures that the airports had in place. Properly thought through, GEEPs will have variations for different needs. Deaf people might need support for alerting, but can then exit the building with everyone else; people with limited mobility might need a temporary (and hopefully not too noisy) refuge, or use of a fire-safe lift. Someone nervous about crowds might just need to wait until everyone else has gone ahead.

Susceptible groups to consider

You should not make any assumptions about what any individual is capable of, whether pregnant, older or younger, fit or disabled. It is not reasonable to insist someone can’t do a job unless you can demonstrate that they miss an ability which is critical to the job, and that reasonable adjustments are not possible.

However, you might need to consider hazards in more detail for some categories of people. In many cases, if you control the hazard adequately for the whole workforce, the hazard for the individuals should also be under control. Similarly, where you make a reasonable adjustment in workplace or job design for an individual, you might find that everyone benefits.

This is not a comprehensive list, but we’ll consider the following groups of people:

- Expectant and new mothers.

- Older and younger workers.

- Physical and mental health conditions.

Expectant and new mothers

“Women of childbearing age” is no longer a useful term, albeit, it is the one in the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (Regulation 16). Girls younger than 10 and women over 70 have had healthy babies. If you are exposing any people to hazards that pose a risk to pregnant or breast-feeding mothers and their children, consider first if you can eliminate exposure to the hazard to protect everyone.

The EU directive on this topic specifically lists certain hazards of greater concern:

- Ionising (eg X-rays) and non-ionising (eg UV) radiation

- Biological agents, such as toxoplasma and rubella virus

- Chemical agents which are mutagenic, carcinogenic, or toxic for reproduction or for organs. For example, mercury and carbon monoxide.

If you are using these substances you should understand the hazards, regardless of whether women of any age are working for you.

I had a client with an x-ray machine in the post room, to check incoming deliveries. The existing procedures included several unnecessary, impractical or dangerous activities, such as washing your hands in bleach (yes, really). I rewrote the procedures and brought in a radiological protection advisor to check the equipment, and my revised procedures. He noted that I had said that any women working in the post room should be informed of the hazards of x-rays to unborn children, and advised to stay away from the x-ray machine when it was in use if they knew, or suspected, they were pregnant. While an admirable sentiment, he said that in reality, it wasn’t necessary. “If there was enough coming out of those machines to harm an unborn baby, I wouldn’t have passed them.”

More common hazards typically considered to cause greater risk to pregnant or breastfeeding women, and their children, include:

- Vibration

- Noise

- Heavy manual handling

- Awkward or sustained postures

- Extremes of temperature

The Council directive also suggests that expectant and new mothers should not do underground mining work or underwater diving if it involves hyperbaric pressures. This is probably not an issue for most of us.

The judgement of risk should be based on personal circumstances. Some women are more fatigued when pregnant and might need to reduce time spent travelling for work. But others are brimming with energy and ideas, and keen to get ahead with work and career before their maternity leave. Some will find it harder to sit, or to stand, for long periods. But so might any worker who did too much gardening at the weekend. Have a process in place for someone competent to have a conversation with a woman when she notifies her pregnancy. Identify if any adjustments are needed, and arrange for a regular catch-up to pick up problems early. Many organisations do this reasonably well during pregnancy, but forget to have the conversation when a woman returns to work. Lurking in the toilets trying to quietly express milk, then hiding it in the team fridge in a flask might not be the best approach.

Older and younger workers

Age can bring wisdom or complacency, so assuming an attitude towards safety based on age is not useful. Evidence from the HSE suggests that cognitive performance continues improving up to at least the age of 60, and then plateaus before declining from the age of 70. However, those still in the workforce at 70 might not fit this pattern. Older people who still work (or volunteer) tend to be fitter and more alert than their same-age peers.

However, with an aging workforce it is worth the time to review your workplace to see if there are any hazards that could be worse for people with age-related conditions. Do any jobs require people to stand for long periods or to climb over ducts in a plant room? Can you reduce the extent to which safety when working at height relies on balance and postural stability?

Another HSE study suggested that poorer visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, field of view and depth perception could cause concerns in occupations where vision is critical, such as driving and responding to changes in control systems.

An older HSE study showed limited evidence that shift work can have a greater impact on more mature workers, but a review of whether your shift patterns follow best practice could be of benefit for everyone.

At the other end of their working lives, lack of experience in the workplace, and in life, can make younger people less risk aware. Alternatively, they might have a better attitude to hazard controls as these have been incorporated into their school science and technology lessons. Do not assume that all young people will be fit and strong. Over the last twenty years, the evidence that adolescents suffer from as much, if not more, back pain and other musculoskeletal complains as adults has grown. Successively, television, videos, computer games and mobile phones have been blamed. Whatever the cause, the hazards of heavy or repetitive work on the development of young people who are still growing should be considered.

Physical and mental health conditions

Table 4.2 is not intended to be comprehensive, but to provide a few ideas you can consider. Highlight the ones that are relevant to your workplace, and add any of your own you come across.

| Condition | Hazards where this might relevant |

|---|---|

| Phobias, such as fear of heights, or claustrophobia | While it’s unlikely that people with a fear of heights are going to end up as a steeple jack, do any escape routes involve balconies or external staircases? Or exits through tight spaces which could be dark? Work in confined spaces, or in low lighting, or in crowded workspaces might be a concern for people with claustrophobia. |

| Anxiety disorders | Psychosocial hazards, including workloads, short deadlines, workplace politics, lack of support, unclear goals, poorly defined roles and uncertainty about the future. |

| Mobility limitations | Trivial slip and trip hazards might become significant. Where a mobility aid (wheelchair, buggy, walking frame) is used, does this force the user into a route that takes them closer to a hazard? |

| Sensory disabilities | Hazards that rely on the senses for alerting, for example reversing vehicles using a sound alert, or flashing beacons providing a visual alert. |

Table 4.2: Relevance of physical and mental health conditions to hazard identification

Interested parties

The categories suggested so far refer to something about a person that might make them more susceptible. However, another useful way to check that everyone who might be harmed has been considered is to categorise people by their role.

The failure of the facilities company in the earlier example was to focus only on their own staff, failing to consider the client staff. To avoid this your written process for risk assessment should include a checklist, tailored for your organisation, which reminds you to consider each type of person. When a new risk assessment (or an accident or incident investigation) identifies a type of person you hadn’t previously considered, make sure that it is added to the checklist.

ISO 45001 requires organisations to identify “interested parties”, which you might also refer to as stakeholders. If you have a list of interested parties, that’s a good list to start this exercise with. Below are some suggestions, but make sure this is tailored to your business. Include children if you are at a school, or even a building site if children can trespass, but not if you work for a laboratory with good security and no staff or visitors under 18.

Table 4.3 suggests the key categories of interested parties to consider. Some of these categories might overlap for you, some won’t be relevant, and you might have additional categories to add. Develop your own checklist, and use it to test every risk assessment for completeness.

| Interested party | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Staff | Permanent, temporary, fixed contracts, freelancers treated a bit like staff, homeworkers, lone workers, remote workers and mobile workers. |

| Contractors and consultants | Project contractors, such as those doing maintenance, servicing or refurbishment, and service contractors such as a health and safety advisor working with the organisation for a fixed period. |

| Delivery and collection staff | From the postal worker who drops mail at reception, to the courier who brings a van load of supplies into the stock room. Or the person who delivers pizza to employees working late. This also includes any workers who collect products from you to take elsewhere. |

| Suppliers | What impact do your requirements have on suppliers? Consider suppliers of services as well as physical goods. For example, an employee assistance programme provider might be impacted by organisational changes that increase demand from your staff. |

| Visitors, customers, clients and service users | Visitors might be signed in and escorted, directed to a specific location (such as in a theatre) or allowed to roam freely (in a shopping centre). Service users include patients at a hospital or GP surgery, a victim reporting a crime at a police station or people using recycling facilities. Don’t forget customers you can’t see. As Donaghue v Stevenson demonstrated, it could be people remote from where the organisation operates, such as people buying a product, or making use of a product paid for by someone else. |

| Members of the public | Your occupational road risk assessments probably consider collisions with other vehicles, but what thought is given to pedestrians forced onto the roads by vehicles parked on pavements, or cyclists expected to ride in a pot-hole ridden gutter to make way for an oncoming vehicle on the wrong side of the road? See R v Jenkins 2012 to see what happens when no consideration is given to the situation other road users are put into by careless parking. |

| Pupils or students | If you run a school or college, you will have considered these as customers or service users. For other organisations, do you have anyone on unpaid work experience, who doesn’t fall into the contractor or staff category? What arrangements are there if parents bring their children into work for a day? |

Table 4.3: Considerations for interested parties

4.4 Conclusion

‘Identifying who could be harmed’ as a separate step suggested that people could be considered, and then forgotten about as you evaluated the risk, selected the controls, documented the risk assessment and reviewed it. As we’ll see in future chapters, you need to consider people at every step of the way.

Chapter 5 attempts to untangle two further steps which can’t be done one at a time – evaluation (or assessment) of risk, and control.

You can use the Contact form to send me feedback. If you’d like to receive an email when I add or update a chapter, please subscribe to my ‘book club’

Alternatively, you can go back to the book contents page.