What is: a control?

First published in Health and Safety at Work Magazine, October 2013

Controlling risk is the core of safety management. Assessing current controls and deciding on new ones is the key element in the third stage of the HSE’s five steps to risk assessment. But what is a control? It appears to be a simple enough word, but it is used in different ways. In her series on basic safety terms Bridget Leathley reviews what defines effective risk containment.

Legislation

In the Health and Safety at Work Act, control applies mostly to dangerous substances, such as explosive and flammable materials. The preamble to the Act describes the need “for controlling the keeping and use … of dangerous substances, and for controlling certain emissions into the atmosphere”.

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations give no definition of control, but refer to it as one element of health and safety arrangements, after planning and organisation, and before monitoring and review. The Management Regs imply that controls include preventive and protective measures (see box opposite). But this inclusion of prevention as a control is contradicted in other legislation.

The Control of Lead at Work (CLW) Regulations and the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) Regulations use identical wording to consider “the effect of preventive and control measures which have been or will be taken” and similar wording to state that: “Every employer shall ensure that the exposure of his employees to [hazard] is either prevented or, where this is not reasonably practicable, adequately controlled.”

These passages imply that preventive measures are not control measures — that if exposure to a hazard is prevented, it does not need to be controlled. The definition of a control measure given by CLW and COSHH reinforces this distinction by stating that a control measure means “a measure taken to reduce exposure to [a hazard]”. But health and safety courses teach that the hierarchy of control starts with elimination (see box), so it seems in common usage we have ignored this distinction by bundling prevention and elimination into the category of controls.

There is some legislative support for this bundling, in that the Control of Asbestos Regulations (CAR) 2012 define a “control measure” to include “a measure taken to prevent or reduce exposure…”

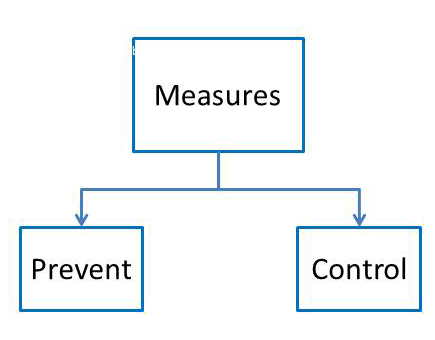

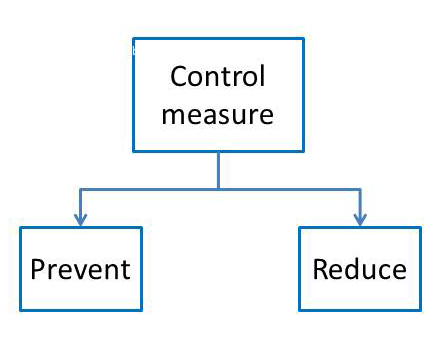

The figures below (Fig 1a and 1b) illustrate the two different uses of the word control in the legislation.into

Fig 1a: Control as a category of measures

Prevention and control are different examples of the category, measures (see Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) and Control of Lead Regulations).

Fig 1b: Control as the group title

Prevention is an example of the category control (see Control of Asbestos Regulations and the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations).

Eliminate, prevent, avoid

Although English definitions might suggest that the use of the term control is more accurate in COSHH and Control of Lead Regulations (Figure 1a) we will for the rest of this article use the more widely accepted meaning of control, including prevention and elimination, from the Management Regulations (Figure 1b).

As well as having to draw in the word ‘prevent’, we must also include other near synonyms, eliminate and avoid. I say ‘near’ synonyms, as eliminate, prevent and avoid are not identical in meaning.

If the hazard is asbestos, it can be eliminated by removing it from a premises. If the asbestos is in an unused cellar, exposure can be prevented by locking the door and ensuring no one gets into the room — but the hazard has not been eliminated. Avoiding the risk suggests merely choosing to stay away.

One popular health and safety course uses an example of a filing cabinet drawer that has been left open, creating a trip hazard. The illustration shows how the hazard can be “eliminated” by pushing the drawer in. However, this is merely preventing exposure to the hazard, or ‘avoiding’ the hazard as the potential for the drawer to be left out remains (remembering that a hazard is defined as something with the potential to cause harm). Elimination of the hazard would involve replacing the filing cabinet with a cupboard with sliding doors which could not create a trip hazard.

Elimination is noticeably not mentioned in the Management regs hierarchy.

The Management regs hierarchy of control

Although often cited as a “hierarchy” the principles of prevention in Schedule 1 of MHSW is a process not a hierarchy, since in cases where the hazard cannot be removed, all the points must be worked through, down to giving instructions to employees. Adapting the work, combating risks at source and providing collective protective measures can all form part of a package of controls. In summary it recommends:

(a) avoiding risks;

(b) evaluating risks which cannot be avoided;

(c) combating risks at source;

(d) adapting the work to the individual;

(e) adapting to technical progress;

(f) replacing the dangerous by the non-dangerous or the less dangerous;

(g) developing a coherent overall prevention policy;

(h) giving collective protective measures priority over individual protective measures; and

(i) giving appropriate instructions to employees.

So what is a control?

A definition of a control on the HSE website is difficult to find. The most concise one is within a section of the HSE website on Some fallacies about ALARP (Fallacy 3). Controls are defined as ‘barriers that prevent the risk being realised’. Since risk refers to both consequence and likelihood, this suggests a control is a barrier that can reduce consequence or likelihood or both, and we will assume this meaning for the remainder of the article.

Inherent safety

Another term relevant to a discussion of controls is “inherent safety”. For a detailed description of the inconsistencies in the way this term is used, see the HSE Offshore safety report OTO 98/151. In brief, inherent safety is used in some cases to refer to preventive and protective controls, applied at the design stage to make a workplace less hazardous in operation. In other cases, it is extended to preventive controls at any stage of the lifecycle, and in still others, it is used simply as a synonym for “my controls are better than yours”.

The HSE’s guidance document on decision making: Reducing risks — protecting people, uses the term “inherently safer” as a synonym for defence in depth, where redundancy, diversity and segregation provide multiple barriers to exposure to a hazard.

If inherently safe (or safer) is to mean anything, it is more useful to restrict it to situations where controls are not dependent on people to do something. Elimination of a hazard makes exposure to it impossible. Anything less and it is likely that people will find a way to become exposed.

Failures to apply controls

In the case of HSE v Davies & Son and Permanent Flooring, the risks of a raised boom hitting a power line were well known, but had not been written down. Following the death of a 19-year-old labourer from an electric shock, the HSE focused on the lack of controls, suggesting that “a very robust written method statement”, along with site markings and a communication process should have been in place.

In 2007, the NHS identified the risk of patients falling out of windows, and required all hospitals to fit window restrictors. The Medway NHS trust identified a lot of missing or broken restrictors on its estate, including one on the first floor at Medway Maritime Hospital. But by 2009, it had not controlled the risk, and a patient fell to his death from the window. Walsall Hospital Trust was prosecuted for a similar incident in 2012, having similarly failed to introduce controls.

In another case, both the contract haulier and its client firm had documented a control — that trailer brakes should be applied before coupling. But they failed to explain it to staff and contractors, resulting in the death of the haulage driver. Both contractor and client firms were fined.

Needs monitoring

Even when controls are established, organisations have a responsibility to check they remain that way.

This is made clear in several regulations: CAR, COSHH and CLW use the same or similar wording: “Every employer who provides any control measure … shall take all reasonable steps to ensure that it is properly used or applied” and: “Every employer who provides any control measure … shall ensure that, where relevant, it is maintained in an efficient state, in efficient working order, in good repair and in a clean condition.”

This means just providing protective guards on equipment is not a sufficient control. Cotek Papers and Loscoe Chilled Foods were prosecuted following injuries to employees who removed protective guards. Cotek was held responsible because the guards were routinely moved for cleaning while the equipment was in operation, so the barrier provided was ineffective. Loscoe had good controls written down on the safe removal of guards, but had not communicated these to its staff.

What is enough control?

The 2010 case of Threlfall v Hull City Council illustrates that even where an employer has carried out a risk assessment, identified a hazard and adopted what seems a reasonable control, a court can decide the control was unsuitable in retrospect.

Threlfall worked for Hull City Council, clearing the gardens of unoccupied council houses. The council risk assessment had identified the hazard of sharp objects, and considered (based on experience) that the most likely consequences could be prevented if the workers took care, and used the gardening gloves it supplied.Threlfall was cut badly when a sharp object cut through his glove and severed an artery and a tendon. The county court and the first appeal found the council had no case to answer; it had carried out a risk assessment and provided controls, and hindsight should not be used to determine the adequacy of the controls.

But the Court of Appeal overturned this result, deciding that reference to Regulations 4 and 6 of the Personal Prototective Equipment (PPE) Regulations put a greater responsibility on the employer to match the type of PPE — that is, the control — with any possible outcome, except where the likelihood is “so slight as to be de minimis” or the consequence is “so trivial that it should properly be ignored”.

Such a verdict makes a decision on the suitability of controls very difficult for a risk assessor.

Objectives met?

In his 2001 book Managing health and safety risk assessments effectively, James Stowe says controls must meet three objectives. They must:

- be effective and reduce the risk to tolerable levels, so far as is reasonably practicable

- meet legal obligations and standards, for example EU standards for PPE, or codes of practice for asbestos, Legionella or lead

- be affordable in time, human resources and money.

Other criteria need to be added to this list. From the description of the control in the risk assessment do I know who needs to do what by when, and how will I be able to check that this has happened?

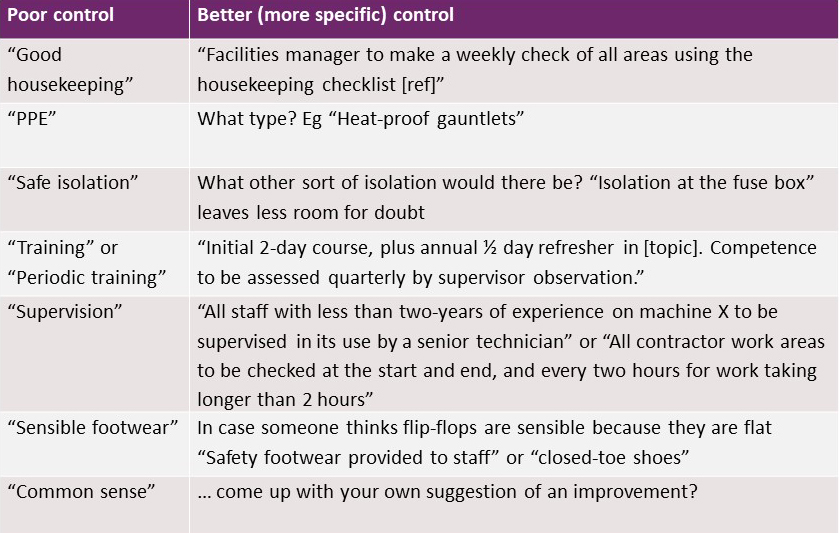

Poor controls

Unfortunately, there are examples even on the HSE website which don’t meet the requirements above. If there is not enough information about the control to monitor it, it is not effective.

For example, in the estate agency and hairdressing examples, the HSE list “housekeeping” as a control. But who will measure the effectiveness of housekeeping, and how?

“Training, instruction and information” is listed as a control in many assessments, but this is no use unless the competence this training and instruction is intended to produce is defined somewhere, and that competence is tested. The box below gives some examples of poor controls, with some more effective alternatives.

Poor controls and suggested improvements

Do all controls need to be written down?

Can an organisation assume that staff will not run in corridors near staircases while checking their make up or looking at text messages? Or do such controls need to be written down?

“Common sense” is sometimes claimed as a control, often when there is nothing more substantial in place. If the only control is common sense, it is likely that either the activity is so low risk it did not really need a risk assessment, or that it requires additional controls.

As in the Davies & Son case set out above, keeping equipment away from the overhead electrical lines seems like common sense, but without written procedures and marked areas for safe working, the control was hard to maintain.

It is reasonable to document clothing requirements where they provide protective value. A risk assessment for maintenance of a boiler listed heatproof gauntlets as a control.It did not say staff should also have their arms covered by normal clothing, and a young technician wearing gauntlets with his t-shirt burned his upper arm.

If clothing requirements are an essential form of protection, perhaps they should be listed in the risk assessment.

It could be argued that you need only document common sense controls where they are known to be weak. Hence, if supervision is currently limited to handing out job sheets, you may need to prescribe a control to monitor work at a stated frequency; if there is already a culture of good supervision, feedback and encouragement, this may be superfluous.

Conclusion

Given the inconsistent use of the term in legislation, it is not surprising that ‘controls’ have come to include anything done to eliminate or reduce risk, wherever this happens in the lifecycle, and whether the effect is to prevent something happening, or to reduce the effects if it does happen. Despite this, there is often too much emphasis on ‘assessment’ and insufficient effort on defining effective controls. Even where controls are well described in a risk assessment, they are not controls unless they are communicated, implemented, monitored, reviewed and where necessary revised. This means defining systems for monitoring and reviewing the application and effective of important controls, and this is where our efforts should be focused.