What is: significant?

First published in Health and Safety at Work Magazine, August 2013. Some case studies and references have been updated where the originals are no longer accessible.

If we are to understand terms like ‘sufficient’ and ‘reasonably practicable’ we must also consider what is significant. Bridget Leathley looks at the many problems of using a risk matrix to determine significance.

In the forthcoming book, I’ll make more suggestions on how to determine significance, without a matrix.

The question

In What is: a Near Miss? (November 2012) we established that accidents involve significant harm, while no harm or insignificant harm qualifies as a near-miss. In What is: Suitable and Sufficient? a suitable and sufficient risk assessment was defined as one which documents the identification and control of significant hazards. In What is: Reasonably Practicable? we were reminded that organisations do not need to make a disproportionate sacrifice (in time, money or trouble) for a relatively insignificant risk.

All of which leaves us with another term in need of a definition: how do we know when something is significant – or insignificant?

Definitions

In 2013, the HSE’s page of frequently asked questions on the subject of risk provided one answer to the question “What is significant?”:

- “Risks which are significant are those that are not trivial in nature and are capable of creating a real risk to health and safety which any reasonable person would appreciate and would take steps to guard against. What can be considered as ‘insignificant’ will vary from site to site and activity to activity depending on specific circumstances. However, we have highlighted some areas which can be considered as insignificant through our Myth of the Month, eg conkers, toothpicks, hanging baskets.”

Excluding only those areas identified in the Myth of the Month rebuttals to press stories of excesses in the name of health and safety management would not take you far. More significantly, the judgement of a reasonable person is not always enough. Any organisation using chemicals, for example, is expected to have a knowledge of the hazards of those chemicals beyond that of the average citizen. It is not surprising that on updating this article in 2021, that quote is no longer available. It is disappointing though that no alternative explanation of the term is provided.

The executive’s 2001 document Reducing Risks, Protecting People (R2P2) set out to explain the HSE’s decision-making process for controlling risk from occupational hazards. In R2P2 the default position is that a hazard is significant “unless past experience, or going through the decision-making process described earlier, shows the risk from it to be extremely low or negligible when compared to the background level of risk to which people are exposed, and the hazard does not give rise to societal concerns”.

Note that, just as we were getting to something definitive – a comparison with background levels of risk, the HSE adds “and the hazard does not give rise to societal concerns”. So the insignificant risk of a worker getting cancer from sitting too close to a computer screen becomes significant because an unscientific scare story garners wide press coverage.

Beyond fanciful

As in R2P2, drawing on experience as a method of determining significance was advocated by the judge in the 2008 case of R v Porter. Here, a child died from an infection acquired in hospital following treatment for a head injury sustained when jumping from some unsupervised steps at a primary school.

Overturning the headteacher’s conviction on appeal, Lord Justice Moses suggests that “the absence of any previous accident in circumstances which occur day after day” might be grounds for considering a risk as “fanciful”.

But in R v Electric Gate Services (EGS) – which we examined in What is: Foreseeability? – EGS was not allowed to use in its defence the argument that there had been no previous similar accident. A nine-year-old visiting flats secured by electronic gates reached between the gate and the supporting pillar to open the gates, using an exit button fitted inside the area for people leaving the flats. As the gate opened, he was crushed and died.

The word significant does not appear in the case report; the original trial judge remarked that the accessibility of the gate opening controls probably did not represent an “appreciable risk”. He therefore directed the jury to return a not guilty verdict. But at the court of appeal, Lord Justice Dyson ruled that “the prosecution did not have to prove that the risk was appreciable or foreseeable. It had to prove that the risk was not fanciful and was more than trivial”. So while the legislation refers to “significance”, the courts use “appreciable”, “fanciful” and “trivial” with no one prepared to explain where these fit on a scale of likelihood, or able to provide direction on how to use these terms in a risk assessment.

“The prosecution did not have to prove that the risk was appreciable or foreseeable. They had to prove that the risk was not fanciful and was more than trivial.”

Lord Justice Dyson in R v EGS Ltd (2009)

Far from obvious

The HSE website states that you need to be able to show that “you dealt with all the obvious significant risks” (Note that the word “hazards” was used in the 2013 version instead of risks). Taken literally, that would mean you need only deal with obvious significant hazards (risks) and, if they are significant but not obvious, it’s fine to ignore them.

But the EGS case above shows a company can be prosecuted for failing to identify and control a less obvious but significant hazard. By contrast, consider the risk of a cave system flooding. That sounds significant and obvious. And if the caves are used by novice cavers, including schoolchildren, the risk of something going badly wrong in the event of a flood would seem even more obvious and significant. However, Leeds Crown Court agreed with the owners of a centre organising such trips that the flooding in a caving system that led to the death of 14-year-old Joe Lister was “unprecedented”. Unprecedented suggests something estimated to have a very low (possibly insignificant) probability. But where the consequences are so major, can such an obvious hazard really be considered insignificant?

Significance is, it seems, in the eye of the judge or jury. Wallace v Glasgow City Council involved Mrs Wallace, a 60-year-old school clerical assistant, who stood on a loo to open a window. The toilet bowl “capsized”, causing her to fall and sustain serious foot injuries.

In 2010, the judge concluded it was reasonable that the school management would not have considered as significant the likelihood of Wallace’s accident. Staff had never advised the headteacher of a problem, and the headteacher, being taller, had no problem opening the window from the floor. However, on appeal, the higher court judge decided that the requirements of the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations make loo windows for ventilation and their safe opening significant, so a risk assessment should have considered this hazard. Wallace was awarded damages of £15,900, cut from £31,800 to take account of her contributory negligence.

Since it is hard to second guess what a court will conclude is significant we must be clear in documenting our strategies for determining significance (a point we will return to) and ensure those strategies take account of hazards which become legally significant because of the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations, the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations and others.

Grow your own

There are two problems, then. The first is that the HSE and the courts do not have an agreed definition of “significant”. In ACoPs, regulations, court judgments and on the HSE website, significance is qualified by adjectives, used to describe quite different situations, and often dropped altogether in favour of terms such as “fanciful”, “trivial” and “hypothetical” versus “appreciable”.

The second problem is that, when these words are used, it is often unclear whether they refer to the consequences, the likelihood or some combination of the two. The consequences of becoming trapped between an electronically operated gate and the pillar are clearly significant, non-trivial and appreciable. But the likelihood of this happening was previously considered insignificant, not just by EGS, but by previous users of such technology who had located the exit button in a similar manner.

If you have a playground with steps, it is inevitable that one day a child will jump from them. But most children would suffer a few bruises at most. There does not seem to be a significant likelihood of the child subsequently dying in hospital from an infection.

We cannot therefore rely on our regulators and lawmakers to define significance for us, and perhaps it is better they don’t.

Organisations often decide significance using a risk matrix. You assess likelihood and consequence on the scales provided, and you interpret the resulting number according to that scale. If it’s a one or a two, it is insignificant; any greater, it’s significant. Simple. But where did your risk matrix come from? Did you adopt one from the (old) HSE website? Did a highly paid consultant sell it to you? Or did someone in your organisation (perhaps you) work it out?

If you want a matrix, there are four key steps to producing one:

- define likelihood categories

- define consequence categories

- decide how you will weight likelihood and consequence

- decide where you will draw your insignificant and intolerable lines.

Previously, the HSE provided an example matrix with likelihood categories of highly unlikely, unlikely and likely, and consequence categories of slightly harmful, harmful and extremely harmful. Such terms are open to widely different interpretations, so many organisations will use a frequency timescales for likelihood – once a week, once a year, once in 10 years and so on – and use the RIDDOR accident reporting regulations’ categories for consequence.

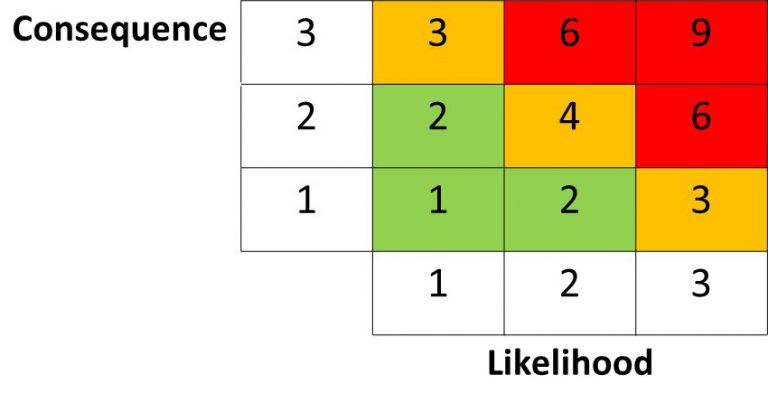

Figure 1: Traditional risk matrix

Step three – deciding how to weight likelihood and consequence – is often missed out. In a traditional risk assessment grid, equal weight is assumed, with likelihood and consequence scores multiplied together to produce a risk score. Figure 1 illustrates this type of matrix.

Staff exposed to hazard A could be killed, so that’s a consequence of 5. However, the likelihood is remote; score that 1. My resulting risk score is 5. On a scale of 1 to 25 that’s pretty low on my priorities.

But do I really regard this as having the same priority as the very high likelihood (5) of staff receiving some trivial injury (1)? They both score 5 when likelihood and consequence are weighted equally, but does that feel right when assessing a hazard’s significance? And is it really less important than a hazard where the consequence is a seven-day injury (3) and the likelihood is a little higher (2), resulting in a risk score of 6?

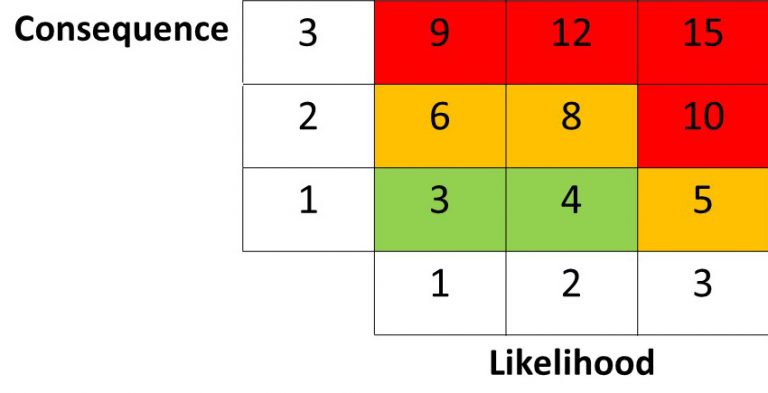

Instead of weighting likelihood and consequence the same, the Charities Commission suggest giving a higher weighting to severity than likelihood. If the risk score is calculated as R = (L x C) + C a low consequence / high probability event would still score 5, but a high consequence/ low probability event would score 10. The Charities Commission suggests that some organisations may wish to go further, using R = (LxC) + 2C.

To see how this would work, see the two examples in Figure 2. A 3×3 grid is used to keep it simple.

In the traditional model, the numbers can be grouped in diagonal bands; as before, high/low scores the same as low/high. In the consequence weighted grid anything with a high consequence is given a higher significance than anything with a low consequence, regardless of the likelihood. Likelihood provides a way of prioritising within a band of consequence, but a high likelihood/ low consequence event can never acquire more significance than a high consequence event. The 5×5 grids allow for more subtlety, but the idea is the same.

In many cases you don’t need a matrix, but if you do use one to prioritise, consider whether a weighted option fits your risk appetite better.

To test whether your preferred weighting model works for your organisation, you need to move to the next step of deciding the organisation’s “risk appetite” or “risk tolerance”, represented in Figure 2 using colours, where green equates to insignificant, red to intolerable and yellow to the as-low-as-reasonably-practicable (ALARP) area (see What is: reasonably practicable).

Figure 2a: Traditional 3x3 matrix

Figure 2b: Weighted 3x3 matrix

Healthy appetite

Determining appetite is an iterative process. Managers, staff representatives and safety professionals need to discuss whether they are comfortable with the results that their chosen scales and weighting for likelihood and consequence produce. Are they prepared to spend more effort to prevent a single high-profile fatality than to prevent a number of low consequence accidents?

Some workforces regard cuts, minor burns and the odd crack on the head as insignificant; I have seen these defined as near-misses. Other organisations might accept that occasionally someone will suffer a serious accident, but would rather concentrate on the high frequency events. If the resulting logic makes people feel uncomfortable, reconsider the weights and the colour bands and start again.

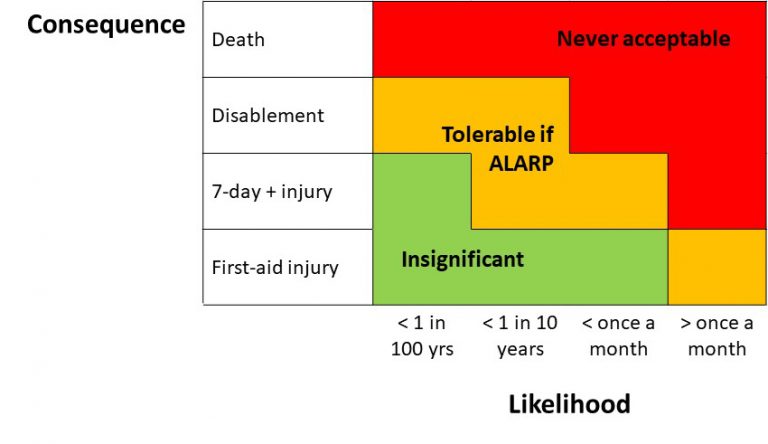

Note too, that you can leave the numbers out altogether. As long as you are clear on how the low to high gradients are defined, the matrices can be presented just using the colours to indicate significance. Figure 3 shows one such example. When creating such a grid, consider each possibility and how you and your organisation feel about it. If you find too many boxes in one region compared with another, you might need to redefine your consequence and likelihood categories.

Figure 3: 4x4 matrix

Down in writing

In Appendix 3 of R2P2 the HSE says it does not expect dutyholders to consider risks if they are “trivial or arising from routine activities associated with life in general”. But the evidence is that, if you get the wrong judge or jury or if the apparently insignificant risk is realised as a result of a breach of another piece of legislation, you need to show that you had some solid processes in place for deciding what was insignificant enough to ignore.

The catch 22 of risk assessments seems to be whether you need to document insignificant risks. Until I have assessed something, how do I know it is insignificant? If I conclude it is insignificant, but don’t write this down, how can I demonstrate I have considered it? The Management of Health and Safety at Work (MHSW) Regulations suggest that only significant findings need to be documented. Is it a significant finding that I have identified an insignificant risk? The code of practice L21 supporting MHSW suggests that “once the risks are assessed and taken into account, insignificant risks can usually be ignored”, but that makes it no clearer. “Once the risks are … taken into account” could mean once I have done something to control them.

R2P2 adds to this confusion by explaining that “risks falling into [the broadly acceptable] region are generally regarded as insignificant and adequately controlled”. Is it only insignificant because it is adequately controlled? If so, the controls that keep the risk insignificant need to be documented. A risk should only escape documentation where it is inherently insignificant. That is, in the normal course of business, the risk is insignificant.

That still begs the questions as to what “normal” is – can we assume that people do not climb on loos, run in corridors or chase pigeons around a factory? Or must we consider only inherent safety, which does not rely on people? This suggests that, even where an important control is behaviour that a reasonable person would regard as normal, it must still be documented.